How long can the baby blues last?

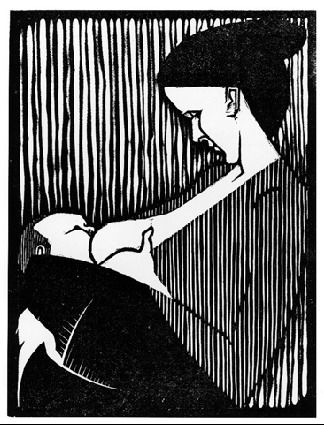

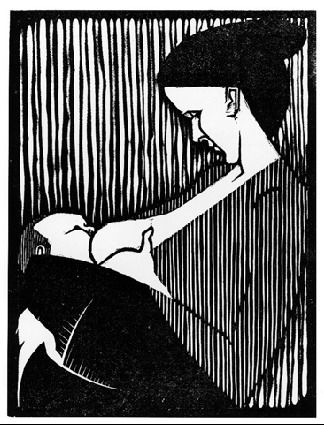

Five and a half years ago, as spring was just starting, I was at home on maternity leave with my beautiful baby girl. Early troubles with feeding were behind us, and I could spend my days in a gentle rhythm of feeds and naps. After each feed, I would prop her up on my knee, talking away and pulling faces while she stared in fascination, the corners of her mouth occasionally quirking upwards in the sweetest of smiles. We took walks together, outside where the spring flowers were starting to emerge and the trees were budding.

I cried every day.

The sun was shining, the flowers were blooming, my daughter was smiling, but nothing could touch the cold, dark hole inside me. It was like walking out in the sunshine wearing a space suit filled with icy water. It had all been triggered by having to stop breastfeeding. However rationally I tried to look at the choice, I felt like a complete failure. When I gave my daughter her milk, those centimetres of plastic bottle between us seemed like an unbridgeable gulf.

Worse, the failure with breastfeeding had been the first time I had ever failed in anything serious I had undertaken. While that should have been a comfort, to me it felt like the first breach in a dam. My daughters’ lives stretched in front of me, not vistas of opportunity, but minefields packed full of chances for me to fail them. Now it had happened once, it could happen again. My daughters deserved better. Sitting with my baby in my arms, I fantasized taking her out in the pram. I would walk along the sunny streets to the midwives practice where, only a few months before, we had listened in rapture to the sound of her heartbeat. I would glance through the door, then, when no one was around, I would quickly go inside. Parking the pram in the warm hallway, I would gently tuck my daughter in under her blanket, kiss her goodbye, leave the envelope on her pram, then turn and leave. Then… I never got as far as what I would do then.

My maternity leave ended, and the complete change of scene and activity helped. Back at work, I was faced with familiar territory, challenges that I knew I was well equipped to handle, tasks that I could complete successfully. The feelings I had been experiencing retreated into the recesses of my heart. But they were not gone.

One subject that has always fascinated me is accident investigation. I find it striking how often an accident has no single major cause, but a number of contributing factors, each one of which when taken alone seems trivial – poor weather, a distracted employee, a software fault – but which combine to have a disastrous effect. The failed breastfeeding was one such factor for me; over time, more appeared, and their combined effect was devastating.

The next place that problems appeared was at my work. I had gained top marks studying engineering, and done well at a succession of jobs in various applied research institutes. Now, frustrated by years of producing prototypes that never got far enough to be of real benefit to anyone, I started to move into project management, hoping that if I took the lead, I could make sure we achieved real results. I was encouraged in this by my managers, who hoped my affinity for planning would help the group as a whole. But managing projects was completely different to organizing my own work. It required skills in communication and persuasion, always my weak points. I could plan the project, but I couldn’t get my plans put into action. So, after years of succeeding in everything I did at work, I was suddenly faced with the situation where I would drive home tense and miserable, with my mind running through all the things that had gone wrong that day.

Another difficulty reared its head when my older daughter started school. Already at the age of two she liked to hang on the railings, staring longingly at the other children, and she was delighted that she could now join them. She quickly settled in, and soon started having play dates with other children. She felt comfortable around the teachers, the children and their parents. I, on the other hand, only had to approach the school door to feel my stress levels rising. As a child, I was often picked on at school for being shy and different. In the years since, I had made a virtue of being unusual, and had been very fortunate to be surrounded by tolerant, open-minded people. Now, faced with a maze of unknown social conventions that had to be negotiated in five-minute playground encounters with other parents – in a foreign language – I rapidly regressed to feeling that everyone was thinking how odd and stupid I was. The only difference with my schooldays being that it wasn’t only my neck in the noose – now I feared my daughter would suffer from having such a strange mother.

The final blow came when my younger daughter was two years old, and we were on holiday with family. On our way to the playground, holding my daughter’s hand, we suddenly saw a dog charging towards us. As my daughter started to shriek in fear, I grabbed her and held her up high – prompting the dog to leap up and try to get her. All in play – but with the playful ‘puppy’ in question being a well-built Boxer, it was only thanks to the bravery of my aunt and uncle that we made it back indoors without serious injury. As it was, our daughter had scratches over her eye, and the child carrier my partner had been wearing was ripped open. For many nights afterwards, our little girl woke up screaming, and she told us about the incident over and over again, trying to process it. For me, it also left scars. I was shaken to the core by my inability to protect her.

All these things came together in my mind. I was a complete failure. I was a failure at my job, I was a failure socially, and – most important of all – I was a failure as a mother. On my way to work every day, I left the motorway on a steeply curved exit ramp, high above the fields. It started to feel tempting not to follow the bend, but to let the car carry straight on and sail off into the air. But that would be a terrible thing to do to the other drivers who would witness it, the emergency services who would have to clear up, the farmer whose field I would ruin. Instead, in my head, plans started to form for a different exit. In my imagination, I ran through how I could arrange things to limit the damage done to others as much as possible. I never came close to putting my plans into action, but the thoughts wouldn’t go away.

While writing this blog, it struck me as totally ridiculous that I had got myself into such a state. I had a good job, a loving partner, two happy, healthy children, and I was contemplating the unthinkable. Yes, I had some difficulties, but it was absolutely nothing compared to what so many people have to go through – poverty, serious illness, war. I was a spoiled brat, and it would be even more contemptible to waste other people’s time mewing about it on the internet. What I needed, now as then, was someone to give me a good slap and tell me to get a sense of perspective, and not be so silly. I switched off my computer and decided I would write no more.

But the fact remained, it had happened. How could that be? Thinking it over, I remembered the start of my first job, when we had received training in how to lift heavy objects properly, and were told the cautionary tale of someone who had slipped a disc bending over to pick up their chequebook. The basic gist was that while lifting a too-heavy object will obviously cause you damage, lifting even a light one can be harmful if you do it in the wrong way. I think that is also how it works with psychological stress. My difficulties were indeed a chequebook compared to the heavy boxes that others were lifting, but because I was handling them in the wrong way, I was putting an enormous amount of pressure on a part of myself that was fragile by nature, and injured by past experiences – my self-esteem. No wonder then, that I was breaking.

What I needed was not someone to tell me that my problems were trivial and I should pull myself together, but someone who could teach me how to handle them in the right way, to shift the load away from my weakest point towards the places where I was strong. Back then, I had not even the slightest inkling of this, no serious hope even that any help was possible. I was extremely lucky, then, that as part of my transition to project management, I was offered coaching. Officially, I went to the coach for help in increasing my visibility and improving my communication skills. The coach did indeed do that – but, despite me never telling her the full story, she also pulled me out of the pit I was in and gave me a new image of myself, not as a dead-end failure, but as someone who was capable of change. The road since then has not been smooth, but I am eternally grateful to her for helping me to take my first steps along it.