My house divided

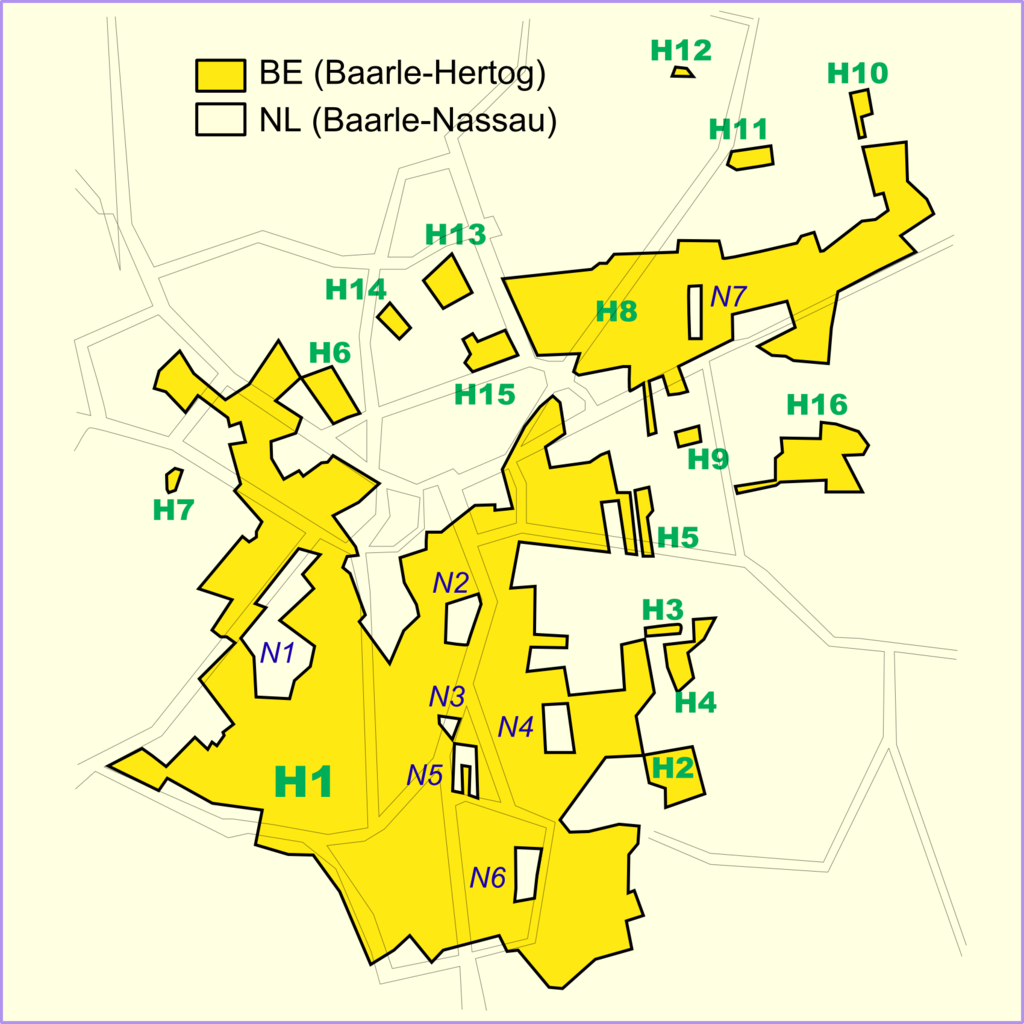

Having grown up in the mainland UK, where the broad barrier of the sea separated us from other countries, land borders have always held a special fascination for me. The idea of being able to stand with one foot in one country, and the other in a completely different one, still seems incredible to me. On holiday, I love visiting ‘tripoints’, where three countries come together at once, and criss-crossing the line of the Berlin Wall sends a shiver down my spine. So, when my boyfriend told me the bizarre story of Baarle, I was intrigued. Baarle is not one village but two, one Dutch (Baarle-Nassau), one Belgian (Baarle-Hertog). The land in Baarle is divided between the two countries in a bewildering fashion. The result is that not only do borders run down streets, they even cut through buildings, so that the house below stands in two countries at the same time. I was charmed by the thought that you could cross into a different country simply by walking through your own living room. It never crossed my mind, however, that I would one day become that house.

Born in Wales with a Finnish mother and an English father, my sense of identity was, unsurprisingly, never linked to a particular country. My fond memories range from chasing my guinea pig round our hillside garden in Cardiff, to taking saunas in my Finnish grandmother’s house on the edge of the woods, to clearing my English grandparents’ council lawn of daisies. Aside of a brief period of fervent (adopted) Welsh nationalism as a teenager, I never really cared much about which country supplied my passport. After leaving school, I took full advantage of the mobility Europe supplied, studying in England and Germany, before working in England, Belgium and, finally, the Netherlands. My choices defined who I was – but in terms of which job I wanted, what type of house, what sort of community to live in. I never thought about it in terms of choosing a nationality.

Now, with Brexit, I’ve opened my front door to suddenly find a line of crosses on the paving stones outside, and turned to see it ripping through my living room. It seems I will soon be put to the question – British or Dutch?

At first, I shrugged my shoulders at the idea. I saw it as just a formality, a piece of bureaucracy, a line of annoying red-tape to be cut through so I could continue my life as normal. The choice would carry no meaning. I would still live in the Netherlands, still visit family in the UK and Finland, still wear my Welsh rugby shirt. I would be the same person.

However, I have the growing suspicion that it will not be so simple. The acrimonious and drawn-out Brexit process, with its many emotional, provocative speeches, has created a state of tension I would never have dreamed possible when I first moved abroad. Sitting in the canteen at work, I listened in disbelief as usually friendly, tolerant colleagues discussed how they would miss Britain, ‘like a hole in the head’. Visiting the UK, we kept our voices down in the pub as we heard the landlord vociferously complaining about his Dutch supplier refusing to deliver any more lager because of Brexit. In this atmosphere, an administrative detail that would have been of no interest to anyone five years ago, has now become loaded with meaning. I cannot simply make the most practical choice for my day-to-day life. Instead, whichever decision I make will inevitably be seen as a statement of identity – more even, it will be seen as taking sides.

But which side? There are Dutch people as vehemently anti-Europe as any UKIP member, while my UK family and friends are almost unanimously pro-Europe. And which identity? The stereotypical Dutchman is very different to the stereotypical Brit, but what unites them is that neither truly exists. An upper-class London businessman and a football-loving Northern factory-worker have as little in common as a bisexual Amsterdam hipster and a Bible Belt resident refusing vaccination, yet each pair share the same flag. How could I even define the two identities in order to choose between them?

Even if this were not the case, there is a more fundamental problem. This is the assumption that a choice is even possible. I am already British. I was born there, I grew up there, it is where my closest relatives live. I say ‘please’, and ‘thank you’, and ‘sorry’ – even when it wasn’t my fault. I wait in line, I don’t interrupt others when they are speaking, and I duck away in horror when people I’ve only just met attempt to kiss my cheek. At the same time, I have become Dutch. I may have lived longer in the UK, but my working life has been mostly spent in the Netherlands. It is where my partner comes from; it is where my girls were born. I travel to work (and to most other places) by bike, I expect everyone to give their frank opinion, and I even sometimes overcome my English scruples to do so myself. I read “Jip en Janneke” stories to my children and fill their shoes with toys at Sinterklaas. I cannot choose between British or Dutch, because I am both, inextricably intertwined.

Just like that house in Baarle, the borders have shifted under me. I haven’t moved an inch, but suddenly I’m perched on a gap between two worlds. In Baarle, the two governments involved cooperate, so the residents can live normal lives. A house-owner may shift their front door to take advantage of a better tax regime in one country, without anyone regarding it as a change of identity or allegiance. In days gone by, in a cafe that straddled the border, there was a table placed across the line, so that notaries could conveniently sign a joint land deal while sitting each in their own country (and, presumably, raise a glass together afterwards). I can only hope that the British and European governments will put the fighting behind them and be as pragmatic as the Dutch and Belgian were. That they will take steps to recover a friendly atmosphere and make agreements that allow my house to remain standing, and my life to continue as normal, the border line running through it nothing more than a curiosity.