Sixteen hours to change yourself

What do you do when you are a complete failure? Either you give up, or you have to change yourself completely. That was the frame of mind I was in when I started my first course of coaching, and giving up seemed by far the most realistic option. The coaching plan was for eight sessions, two hours each. It seemed impossible that sixteen hours would be sufficient to renovate a wreck like me. But my coach was optimistic – it could be done. To my utter amazement, she was right. Eight sessions later, I was confident enough of myself to set my sights on a promotion. What did I learn in those sixteen hours that made such a difference?

I haven’t done that yet, so maybe I could do it

In the coaching material I received there was a picture of Pippi Longstocking, with the quote, in large letters: “I’ve never done that before, so I’m sure I can do it”. I found this toecurlingly embarrassing in its naive optimism. When faced with something new, I was always filled with panic. I remember the first day of my very first job, when I was given the assignment to build a preview application for a virtual studio, and I sat at my desk paralysed with fear. A few months later, I had a previewer up and running. Talking the past over with my coach, I had to admit that most of the times I had tried something new, it had turned out fine. I realised, too, that I had been growing and learning all my life, and there was no reason to believe I was incapable of it now. I still couldn’t choke down Pippi’s childish wisdom, but I could live with my own version – ‘I haven’t done that yet, so maybe I could do it’.

But what if I failed?

Failure is not an option – it’s a necessity

Failure is my worst nightmare. Quite literally – I regularly wake up in a cold sweat after dreaming that I have messed up something important and that everyone is furious at me. As a result, I have always arranged my life to avoid failure as much as possible. The first insight my coach gave me about failure was simple but brilliant: limiting my life in this way was also failure – failure to meet my potential. If I never attempted something that went wrong, then I was not attempting enough. The choice was not between success and failure, but between the risk of failure by action or the certainty of failure by inaction.

The second insight was one I had been mouthing since I was a child, but clearly never truly understood: “You can learn from your mistakes”. In my mind, that had always meant learning from them in order to never repeat them again. The idea that mistakes can be the route to completely new knowledge was a breath of fresh air. Think of Fleming’s discovery of penicillin through his failure to keep his lab tidy. To keep learning new things, I needed to keep making new mistakes.

The third insight was equally obvious – everyone around me regularly made mistakes. From my boss, to my family, to my partner, people forgot things, turned up too late, and misunderstood what was going on. Somehow, while often getting irritated by other people’s errors, I had never thought to ask the logical question – if everyone around me is messing up on a regular basis, then why should I have to be perfect?

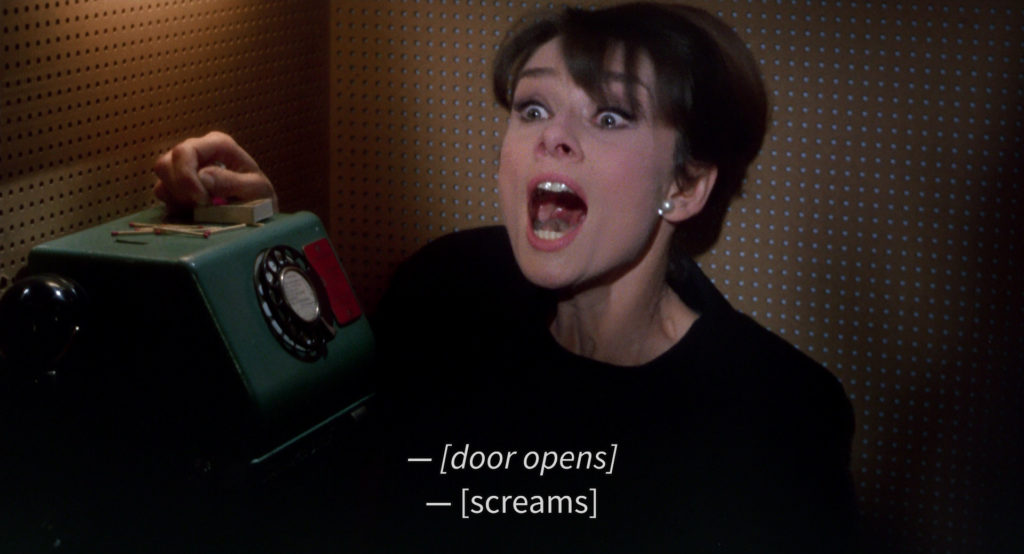

This was all well and good for my brain – but the mere thought of failing twisted the pit of my stomach and filled my head with visions of jeering crowds. My coach traced that one back to being picked on in childhood, and posed the crucial question – had anyone in my workplace ever mocked me for a failure? The honest answer was – no. I was holding on to teenage reflexes that were way out of date. Once, they had protected me, now they were needless barriers. It was time to fail without fear.

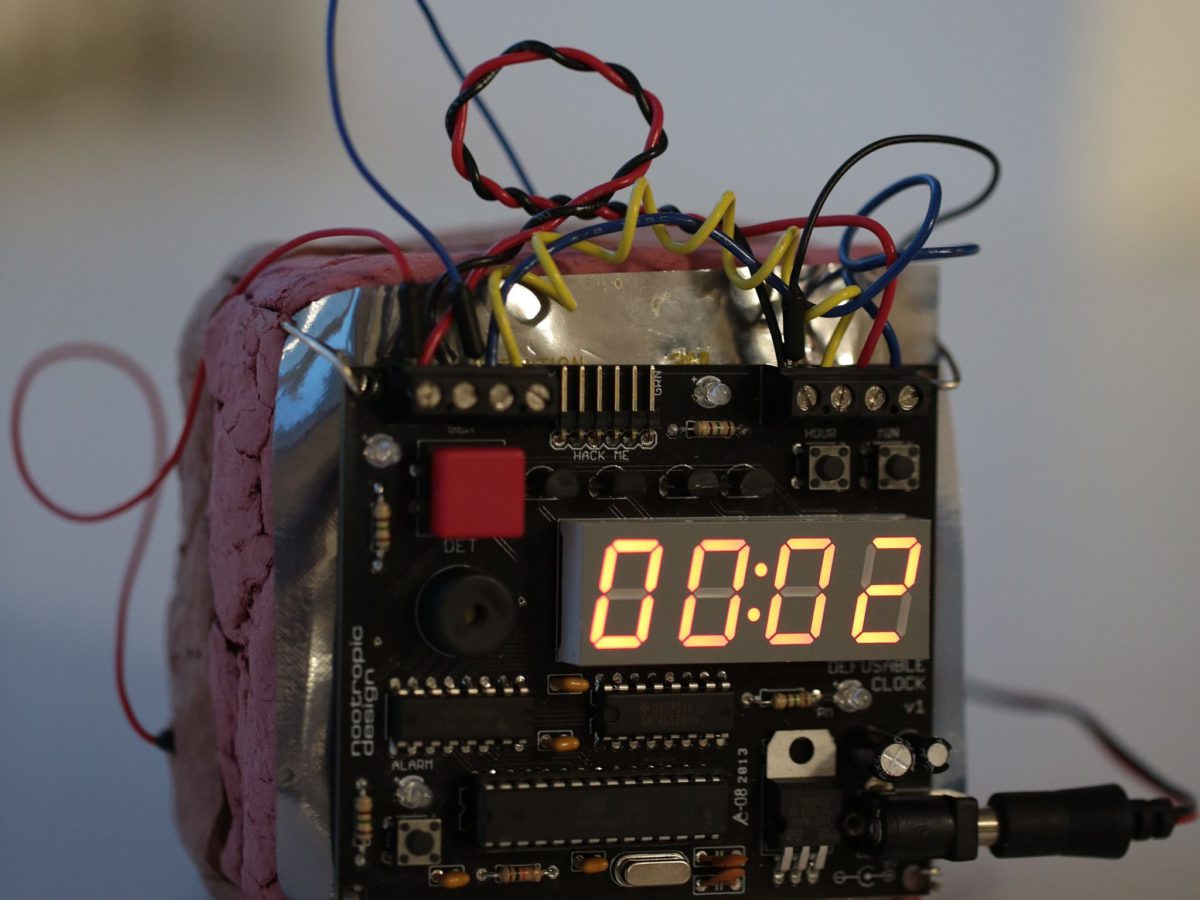

Turn on the subtitles

Each year during my appraisal the same criticism kept coming back – I was too quiet. It was always a source of frustration to me. Was I supposed to talk when I had nothing to say? Often, I was thinking things over, and by the time I knew what I wanted to say, the moment had passed. When I did try to speak, I regularly couldn’t get attention. Finally, other people had the tendency to speak or act for me while I was still deep in thought. My request to my coach was clear: help me to become someone who can respond quickly. I didn’t believe it was possible – and my coach agreed. She drew a ‘cake’ model, split into four sections: thinking, feeling, wanting and doing. I was clearly a thinker. Everything else – feelings, actions, desires – were first channelled through my thoughts. And that was never going to be quick. Her solution was completely different – turn on the subtitles.

While I was busy thinking, the outside world didn’t have a clue what was going on inside me. It was natural, then, that they would move on with the meeting, talk over me, or take action themselves. ‘Subtitling’ meant giving them a window into my thought processes. ‘Hang on a moment, I’m thinking’. ‘I’d really love to do that, but first I need to work out how it could fit with my other projects’. Even when I really didn’t have anything to say, I could show that I was involved and interested. ‘Definitely’, ‘I agree’, ‘Oh, how terrible for you’, ‘Yes’, ‘Really?’, ‘Uh-huh’. These comments didn’t contribute anything useful, so I would never have made them before. But now that I did, I noticed a big difference. People spoke to me more, and it was easier to get attention in a meeting.

I also realised how often actions could be misconstrued. You can have good intentions, but it’s no good if no one knows that. Subtitling helps here, too. ‘I want to make sure I give you the right information, so I’m not going to answer until I’ve received all the data’. It came in handy with other parents at school, ‘Sorry, I have a terrible memory, can I just check where you live again so I’m sure to be there on time?’. It was even useful at home. ‘One minute, I forgot to switch off the computer’ avoids a whole load of irritation about why you’ve disappeared just when dinner is on the table, and ‘Mummy’s going to take Blue Bear to give him a wash, do you want to give him a kiss before he goes?’ can stave off a tantrum before it starts.

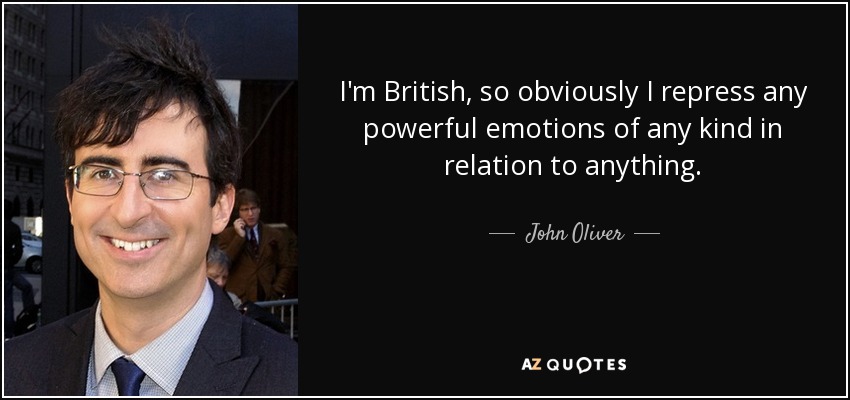

Emotions are powerful

As far as emotions go, I’m as British as they come. I hate to be seen crying, and I feel ashamed if I lose my temper. To me, it always seemed professional to keep my feelings in check, and to behave in a business-like way. It was a disaster, therefore, when I almost burst into tears during a disagreement with my new boss. At our next review meeting, he astonished me by saying how impressed he had been, and that he had never realised I was so passionate about my work. In discussion with my coach, I realised that completely repressing my feelings didn’t make me look professional – it made me seem boring and indifferent. A controlled display of emotions, on the other hand, would help me to connect with others. It could also help me to persuade them. People are far more willing to help you with a problem if they see that it truly matters to you.

I need to take control

As the younger child by several years, I’ve always been used to others being in charge. In school, at university, and at my jobs, I did what I was told. Now I became frustrated that there was no clear line on what I should do. Plans for my future changed as often as the group heads and shifted with the latest market trends. Skills that I learned became superfluous, ideas were first pursued and then dropped. At the same time, as project manager I had the responsibility for ensuring project goals were achieved, but I had no higher status than my colleagues working on the projects, so I felt unable to push them to do as I asked.

My coach encouraged me to stop being a passenger, and to get behind the wheel instead. I didn’t need any higher status in the group to justify asking for what I needed to be able to do my job. I also couldn’t count on others to ensure my career was going in the right direction. If my ‘cheese’ had disappeared, then I couldn’t sit around waiting for it to magically come back, I needed to take my lot in my own hands and go out in search of it.

On completing my coaching, I was full of enthusiasm. I felt I dared to try new things and was willing to entertain the possibility of surviving some failures. Experiments with subtitling and revealing emotions had shown that I could greatly improve my contact with others, while still being the same person inside. Taking control was harder: after years of following others, I had very little idea of what I actually wanted. After some thought, I decided that it was important to me to achieve real benefits for others. To do that, I felt our whole way of working needed to change, so I decided to go for the role of chief researcher. Pleased with my progress during coaching, my manager supported me in working towards that ambition over the coming years.

Sixteen hours hadn’t made me into a new person, but by changing my outlook and skills, it had changed my life.