Perfection: The perfect solution

We live in a world where, increasingly, we expect perfection. Perhaps we don’t always admit that to ourselves, but it is evident in our behaviour when things go wrong. The smartphone that breaks, the train that is delayed, our child’s poor test scores, the outbreak of a virus. When these things happen, the predominant tendency is to cast around to find the person responsible, then complain, protest or sue to obtain an apology, compensation and – most of all – a promise that it will never happen again. New regulations, better technology, improved education, more effort, more money. If we only apply enough of these, then nothing need ever go wrong again. When improvements fail to materialise, we look elsewhere for perfection. Switch suppliers, move to another country, find a new partner. This constant quest for perfection is so ingrained in our society that we rarely even notice it, let alone challenge it. This series of posts will look at the effect of our desire for perfection on various aspects of our lives. This post: the perfect solution

Many people find week-day mornings tough. But with children they are akin to directing a major military assault. At our house, we have an hour and a half from knocking on our children’s bedroom doors to delivering them, and their requisite baggage, to the creche. It seems ample, but in reality every small step along the way can be derailed: when it’s more tempting to play with modeling clay than to get out of their pyjamas, when their favourite jumper turns out to be in the wash, when they take umbrage at the choice of their morning snack for school. One morning recently, we hit a roadblock when our younger daughter refused to put her bottle of water in her school bag. She didn’t like that bottle, she wanted the other bottle. When we reminded her that it had leaked all over her school bag the day before, she still balked. Where we saw a clear-cut choice – a wet bag or a second-best bottle – our daughter was convinced that there must be a solution that would allow her to take her favourite bottle without soaking her bag. And she wasn’t going to move until we had found it.

The belief that the powers-that-be are, for some incomprehensible reason, deliberately withholding perfect solutions from us is one that I think many of us – consciously or subconsciously – retain as we become adults. It would go some way to account for our distrust of experts. The expertise accumulated over centuries has given us incredible capabilities. We can fly, we can transplant organs to save dying people, we can send information around the world at the press of a button. It seems like anything is possible. As non-experts, we usually don’t understand how the underlying processes work. So, when The Expert tells us that something that we want is impossible, we are instantly suspicious. Surely it can only be down to the expert’s incompetence, or their own stubborn willfulness. This is parodied painfully accurately in “The Expert – seven red lines”, when a team requires their expert to ‘draw seven red lines. All of them strictly perpendicular; some with green ink and some with transparent’. The team members refuse to accept the expert’s patient explanation as to why this is impossible. He is an expert, he should be able to do anything.

We carry this same attitude over to the situations were something is possible, but at a cost. It was possible for my daughter to have her favourite bottle, but at the cost of a wet bag. But, just like my daughter, we don’t want to accept those costs. We want better hospitals without paying taxes to fund them, safety from crime and terrorism without our civil liberties being impinged on, new technological gadgets without factory pollution. Liberated working women who have a home-cooked meal ready in their spotless kitchen when the kids come home from school, cheap clothes without slave labour, our favourite product always in stock at the supermarket without tonnes of unsold food being thrown away.

In reality, life is a constant trade-off. This is enshrined in various scientific laws, but also in simple folk wisdom: ‘There’s no such thing as a free lunch’. But instead of accepting this, it is easier to blame someone else for their failure to find the perfect solution that we are convinced must be out there somewhere. This situation was succinctly described by Jan Benjamin and Jan Meeus in an article they wrote when heavy snow had largely shut down the public transport network in the Netherlands, causing a great deal of indignation among travellers. People want the trains to keep going, no matter what. But they don’t want to pay extra to make that possible – and if an accident happens, then they blame the government, rather than accept the greater risk inherent in their choice to travel in severe weather conditions. This naïve belief in a perfect solution prevents us from seeking the optimal solution that would maximise the benefits and minimise the costs, because we refuse to accept any costs at all.

The coronavirus crisis is a perfect example. We don’t want anyone to die from the virus, yet we want to keep our jobs and homes, to be free to meet our families and friends, and to be able to go to hairdressers and restaurants. The Dutch government also doesn’t want anyone to die, but seems to believe that the virus can be beaten ‘for free’ by working from home and cheerfully holding Zoom parties, ignoring inconvenient facts such as that many jobs cannot be done remotely and that Zoom cannot satisfactorily fulfil the human need for physical contact and social interaction, let alone sustain vital processes such as education and medical treatment. The reality of the trade-off that is being made between damage to health and lives due to the coronavirus, and damage to health and lives due to the measures against the coronavirus is largely ignored, making it impossible to discuss whether it could perhaps be altered to minimise the damage overall.

At the same time, we pounce on other countries who choose a different trade-off, vilifying Sweden for their lenient approach, and China for their draconian approach. We don’t want to see the reality, that every approach has its imperfections, and therefore its losers. A draconian approach is ‘the wrong approach’ for the entrepreneur who loses their business (and home) because of the corona restrictions, for the grandparent who dies after months of loneliness in a nursing home, for the child with cancer who is diagnosed too late for effective treatment. But the lenient approach is ‘the wrong approach’ for the entrepreneur who loses their business (and home) because their employees all catch corona, for the grandparent who dies of the virus, for the child with cancer separated from their parent who is treating corona patients.

In the absence of the perfect solution now, we put our faith in the perfect solution just around the corner. First in the development of test and trace systems, then the corona app, then vaccines. Despite near-miraculous achievements in the rapid development of tests and vaccines, we are still waiting for the promised delivery from the lockdown, and even in the future the magic bullet of the vaccine is unlikely to live up to our hopes. In fact, our discovery that vaccines are less than perfect is prolonging the lockdown, as people become wary of receiving a vaccine, and politicians play safe by slowing or even stopping vaccinations. As Rosanne Hertzburger described in her article in the NRC, what is in itself good and responsible advice to ensure vaccine safety totally ignores the bigger context of the large number of unvaccinated people with corona currently fighting for their lives in intensive care. To me this shows an incredible lack of perspective, akin to a fireman refusing to rescue people from a burning building because his ladder has not had its safety inspection that month. He worries that someone could fall and get hurt – but the people burning to death in the building are not on his conscience. Every day we continue to believe in the myth of a perfect solution is another day that we fail to work on a realistic, sustainable, long-term approach to living with corona.

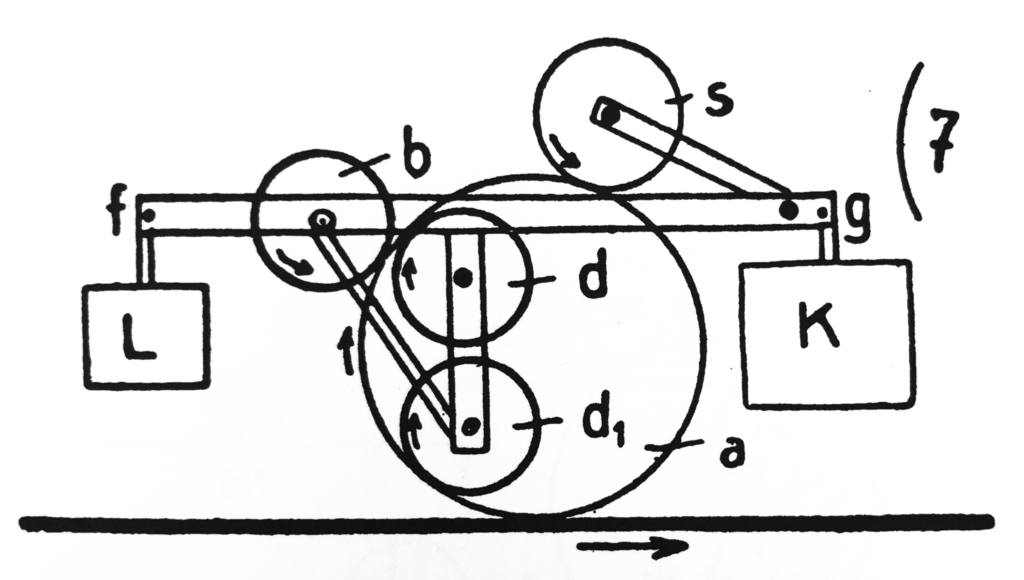

While perfect solutions don’t exist, it’s certainly possible to come up with better solutions. Lots of time and effort is often expended on this process. Often, busy with honing our solution to get it closer to perfection, we totally forget to ask at what point a solution is sufficient. I will never forget a project I once worked on to develop a machine for sorting seedlings. Lengthy discussions with plant experts yielded a long list of features to be measured, many of them extremely hard to measure automatically. We struggled to build as many of them as we could. The actual – very successful – machine measured one single simple feature. “Good enough” is nowhere near perfect, but it is a lot quicker and easier to achieve. As George Patton is misquoted as saying, “A good plan today is better than a perfect plan tomorrow”.

Finally, the hunt for the perfect solution is based on one huge assumption – that our intervention is beneficial. We are addicted to action. In particular those in authority like to be ‘seen to be doing something’. Observing a situation, awaiting developments, or refraining from action entirely are not seen as valid options. This despite the principle of non-maleficence – ‘first do no harm’ – having been enshrined in good medical practice for thousands of years. Sometimes we must accept that if our actions won’t help or may even make matters worse, then doing nothing is the wiser course. As the saying goes, “The road to hell is paved with good intentions”, neatly exemplified in the cobra effect. If trying to get rid of cobras is going to lead to there being more cobras in the end, then you’ll wish you’d just left them be.

Parents who try to solve everything for their children, who constantly smooth their path and remove any obstacles, are often mocked for being ‘helicopter parents’ or ‘lawnmower parents’. Every child has to make the discovery that Mum and Dad are not all-powerful beings who can solve every problem with the wave of a wand. Learning that some things that you want are impossible, that what is possible comes with a price tag, and that there are times when the price is too high, is a vital part of growing up. “You can’t always get what you want” and “Do you realise what that costs?” are phrases I regularly repeat to my own children. More and more, I begin to think that these are lessons for which many of us could do with a refresher course.