The ordinary feminist: the workplace

I am a woman who works as an engineer. I am proud of that. At the same time, I am aware that I don’t actually have any right to be proud. I didn’t choose my career as part of a selfless feminist crusade, but because it was what I wanted to do. In that respect, I am no different to my schoolfriends who chose to become hairdressers or nursery assistants. Nor have I blazed a trail for the rights of women to be engineers. I’ve simply gotten on with my own career, never giving my gender much thought.

Getting ready for my university interviews, a career guide advised me to prepare for the question ‘Why, as a woman, have you chosen to study engineering?’. A totally insane question, in my opinion, as while I considered pretty much every other possible factor when choosing what to study, I never took my gender into consideration, any more than my hair colour or my liking for spicy food. They were all equally irrelevant. Having prepared this answer, I was ever so slightly disappointed that, out of six universities, my gender was brought up in exactly zero interviews.

I started my course as one of three women in a group of nearly a hundred first year students. I saw this as more of an advantage than a disadvantage. It was quite nice to be able to roll into a morning lecture with uncombed hair, no make-up and scruffy clothes, safe in the knowledge that no one would say a thing. (Whether that is a characteristic of male students in general or of tech nerds specifically is a question that I can’t answer). Neither my professors nor my fellow students ever implied that I wasn’t capable of doing the course. When one of my lecturers wryly commented that my soldering wasn’t the worst he’d ever seen, there wasn’t even the slightest hint of ‘women can’t solder’ (He was right about the soldering, by the way).

Comfortable in this atmosphere of acceptance, the email that landed in my inbox during my second year came as a shock. The engineering society had requested students to join the organising committee, and only two had responded. Both women. This new email was a plea for more applicants – ‘if we don’t want to spend our social events sewing and doing the washing up’. I was one of several students – both men and women – who responded in anger to this email. Don’t be so touchy, it was just a joke, we were told. When I continued on the subject, heated but still civil, I was threatened with being reported to the university authorities. Too inexperienced to recognize how ludicrous this threat was, I duly shut up. Even now, far too many years later than I like to count, the memory of being silenced in this way makes my blood boil.

This is the one and only overtly sexist incident I have ever experienced in my career. I am truly fortunate in this. However, that doesn’t mean that my work environment is free of sexism. The trouble is that the behaviour is far more subtle than a crass email about women and their supposed obsession with household chores.

How, then, do I know that there is sexism at work at all? There’s one very good reason – I am guilty of it myself. When I am told that a programmer is coming for a meeting, I expect a man. When I am introduced to a woman in a pretty dress at a conference, I find myself explaining my work in simpler terms than I would do to a man in a geek t-shirt. I catch myself at it – and I spot others doing it as well. Just the other day, a colleague reported back to our team about a candidate for a vacancy as programmer. “She has lots of experience…” – “She?”, interrupted one of the other programmers. The current team is actually fifty-fifty. Yet apparently it is still a novelty that a programmer is a woman.

Sexism, in the places that I have worked, never wears its colours on its sleeve. No one ignores a woman in a meeting because she is a woman, no one asks a woman to take notes because she is a woman, no one volunteers a woman to manage the team, arrange user feedback or sort out a leaving gift because she is a woman. Yet, over time, I’ve noticed that men’s opinions are listened to more readily: I’ve seen enough occasions when a woman’s suggestion is ignored until repeated by a man that the ‘Invisible Woman’ sketch makes me want to both laugh and cry. And it just so happens that it’s mostly the women who take notes, and strangely enough they seem to end up doing the user feedback, the leaving gifts and the management too. A certain kind of management, that is: the sort of management that is a lot of work but makes no difference whatsoever to your pay or status. My women colleagues spend far more time on ‘invisible work’ than the men do. Then there is simply the ‘othering’, setting women colleagues apart. Such as the ICT boss who, apologising for the stuffiness of a small meeting room, said “We were here with seven men. And Tricia”.

I think the evolving attitude of engineers to their work plays a role here. The ‘old guard’ consists, for a large part, of engineers who love gadgets and programming for the sake of it. Whereas the ‘new guard’ is also interested in the broader context of their technical work, such as business cases, effective team processes, ethical design, user-driven development. It just so happens that the old guard is mostly men, whereas the new guard contains an increasing proportion of women. But once a woman has voiced an interest in the non-technical context of her work, it is an excuse to push any and all non-technical work towards her, while reserving the hardcore technical work for the men. Ever since I mentioned that I like working together with users while developing my code, I have had to fend off suggestions that I might like to take on this work for the other programmers. In this way, women run the risk of being edged out of technical work, strengthening the prejudices of the ‘old guard’ that women were never really suited to technical work in the first place. It’s like being a surgeon who, unlike her old-school colleagues, takes pride in checking up on her patients after their operation. Only for it to be suggested that she might like to check up on all post-op surgical patients in future, leaving the surgery to the men.

This sort of sexism is very hard to bring up. An individual incident is too easy to explain away: ‘Sorry, I just didn’t hear what she said, she needs to speak up more’ or ‘but Pam knows Steve best, so she can pick out a suitable gift’. Not to mention the dreaded, ‘Oh, but Kate is so good at taking notes!’. This sounds so innocuous, even complimentary – until you realise that it’s only used for the sort of work that no one else wants to do. At least, I have yet to hear, ‘Oh, but Peter is so good at developing computer vision algorithms!’.

It’s only when individual incidents pile up that trends become apparent and underlying prejudices can be detected. But discussing trends is problematic, as any statement of ‘it’s always the women who organise the gifts’ will be cried down unless you’ve kept meticulous track of individual occurrences. Recording incidents may be the sort of thing advised by professionals, however, it is a quick way to make yourself very unpopular in your team. Who wants to work with someone who, like a traffic warden, has a little book in which they note down points against you?

As a teenager, I always thought I would know what to do when faced with sexist behaviour: slap them in the face and call them a male chauvinist pig. But I don’t work with male chauvinist pigs who deserve slapping; I work with very nice people who are totally unaware of the effect of their behaviour. Often they don’t even know that they are doing it. Criticising colleagues is difficult in general, but it’s even harder to raise anything related to sexism because this is such a sensitive, loaded subject. It is a measure of just how sensitive it is that, of all the blog posts I have written, this is the one I have been most hesitant to publish. Criticism about sexist behaviour is rapidly perceived as an accusation and an attack on someone’s character. How, then, to bring up such behaviour without destroying team spirit? I don’t know – so I don’t do it.

It’s also tough to trust my judgement as to what is and isn’t sexist behavior. In particular as I am by nature shy and self-doubting, so it is easy to think that I am passed over because I don’t have enough expertise or because I am not assertive enough. That it’s not because I’m a woman, but my own fault. It is only when talking to other women that it becomes possible to verify that it’s not imaginary, or the logical consequence of my shortcomings.

Starting in a new job, I met a member of another team that we worked closely with. A man with a partner and a child, just as I had. He had a jokey style, teasing his colleagues, both men and women. Used to that sort of banter from my student days, I felt perfectly comfortable with it. Then, during lockdown, I needed this guy to help me with a technical issue. He did – but his comments over email became rapidly inappropriate. I first tried to deflect them with jokes, then broke off the communication, blaming myself for ever having joined in with the teasing, as I had clearly given him the wrong impression. That is, if this email exchange wasn’t just a big joke, too, which I had simply misunderstood by being over-sensitive.

It wasn’t until lockdown was over and a new colleague approached me with ‘a problem with a guy on the other team’ that it became clear that his behaviour wasn’t down to me. Even so, the two of us struggled with how to handle the situation, still not sure if the behaviour was sufficiently inappropriate or not, and worried about upsetting the teams. After a confidential discussion with HR we opted to talk it over with the man in question. He couldn’t understand at all what the problem was – his girlfriend liked this sort of humour, and it would be too dull at work if he couldn’t joke around. He wasn’t angry or upset, however, and agreed to be more careful with his behaviour.

More than a year on, however, there was a third colleague experiencing the same problems with this man. We escalated the issue to his boss, who took no action. Worse, there was a vacancy in his team, so we faced the moral dilemma of whether we should warn any women candidates – an impossible choice between loyalty to our current colleagues and loyalty to a future colleague. My women colleagues are all conscientious and care about the team and our organisation. It is ironic to me that it is precisely our sense of responsibility, our concern for others, our respect for rules that renders us powerless in such situations.

This inevitably reminds me of that student council incident so many years ago, when my conditioning to be well-behaved and not cause trouble effectively silenced my complaint. Looking back, I realise that it is not the only time in my career that I have been silenced. Once I worked in a team with a colleague who was highly critical of how things were run, and vocal in her criticism. I agreed with her, but was too shy and nervous to do more than support her point of view on specific questions. On resigning to move abroad, however, I saw an opportunity to help matters by listing my concerns in my resignation letter. My boss gave little reaction when he read it. Later the same day, I heard that he had summoned my colleague, blamed her for the content of my letter, and threatened her with dismissal. Both of us were effectively silenced, her by a direct threat, me out of concern for her. Looking back now, I wonder if he would have behaved in the same way if we had been men.

Regardless of whether or not his behaviour was sexist, his aggressive and manipulative reaction to my feedback has had a lasting effect on my willingness to speak out and be critical. I was horrified that this could occur in a workplace that had, up to that point, seemed very open and accepting.

I have begun to feel that there are two types of acceptance in the workplace. One is a sort of baseline acceptance, which has to do with the norm within the workplace. The second is an acceptance of criticism, which has to do with how willing people are to discuss whether their behaviour actually fits the norm, and to allow that norm to be challenged. In the institutions in which I have studied and worked, the baseline acceptance was very good. I was accepted as a woman engineer, I was part of the team, my abilities were respected. Yet of the three occasions that I have voiced serious criticism, twice I was silenced by an angry backlash, and on the third occasion the criticism was listened to but no actual action was taken. In this way, it is easy for organisations to appear to be diverse and accepting – as long as they are never challenged.

In retrospect, I think my smooth career path may have had a lot to do with the fact that, my gender aside, I fit the norm of an engineer very well. I am introverted, geeky, outwardly unemotional. If I had been an outgoing extrovert with a liking for neon pink dresses and high heels, if I had cried when I failed to get my code working, then jumped up to dance around the room once I succeeded, if I had been forceful when I saw the need for improvement, then I might have found my environment much less accepting. An organisation that welcomes women at the price of expecting them to shut up and conform may appear on the face of it to be open and accepting, but is anything but.

This lack of acceptance of criticism makes me extremely reluctant to bring up sexist issues. I fear that at best it will be a lot of bother for nothing, and that at worst it can have enormous repercussions. Reinforcing my reluctance is the fact that I am incredibly lucky in my work and in my colleagues. Listening to horror stories of women suffering verbal abuse, being systematically undermined in their work, sexually assaulted or unfairly dismissed, what I have encountered seems almost too trivial for words. Should I put our pleasant team atmosphere at risk for the sake of some minor sexism? On the other hand, it does affect the work of me and my women colleagues, and I have two daughters who will be entering the workforce one day, who I would not want to be treated this way.

I also wonder, is it actually so minor? My tendency was always to regard such incidents as the last remnants of sexism, the sporadic pockets of resistance in a war that was already won. Yet I find the resurgence of sexism around the world very worrying. I read with horror of women losing their ability to work, study, or even control their own bodies, basic rights that had seemed to be so secure and self-evident. Perhaps ignoring small sexist incidents is like neglecting routine maintenance, allowing the cracks to grow and opening the door to a future catastrophic collapse of the comparative equality we have gained.

The other factor to consider is that if I and my women colleagues don’t question the behaviour in our workplace, then our colleagues will stay within their comfort zone, surrounded by people who conform to their norm. They will never learn the benefits that can arise from inviting in someone who does things differently, who asks why you do things the way you do, who challenges you to try a new perspective. As the Dutch say, ‘wrijving geeft glans’ – ‘friction gives shine’. Engineering – or any other discipline – will only truly become diverse by including people who are different in what they do and how they think, not by having more of exactly the same type of people who happen to have superficial differences of skin colour or gender.

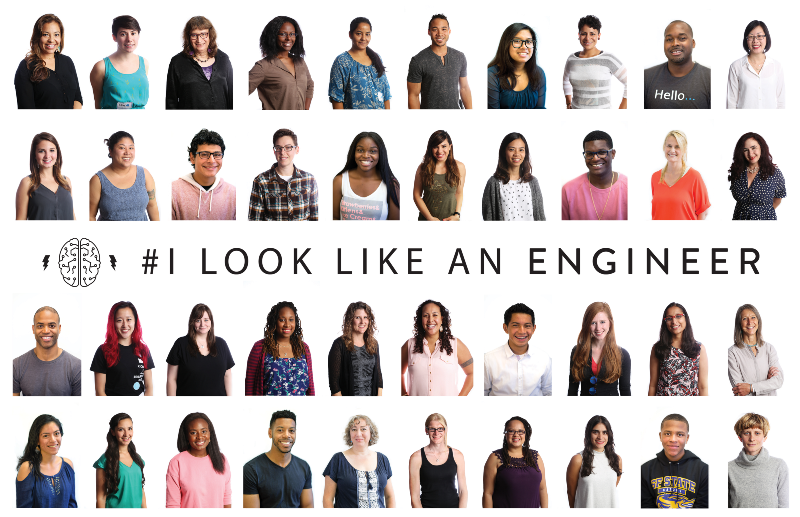

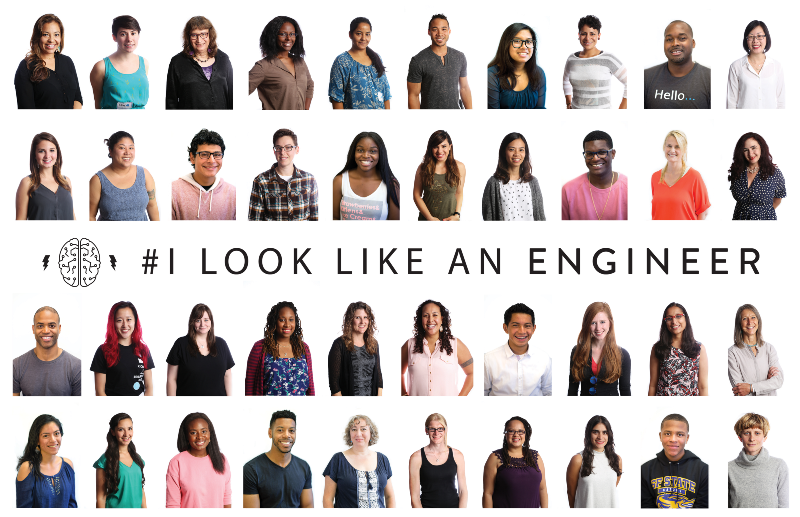

In the past, there were women who went to prison, starved themselves, and even died in the fight for equal rights. Whereas I am reluctant to rock the boat out of fear that I will join the others in the water. How, then, can I be proud to be a woman engineer? The answer, of course, is that I can’t. Not until I can become worthy not only of the hashtag ‘I look like an engineer’ but the hashtag ‘I behave like a feminist’.

This post is part of the ‘Ordinary Feminist‘ series. The next post: The relationship.