How to be a good detective

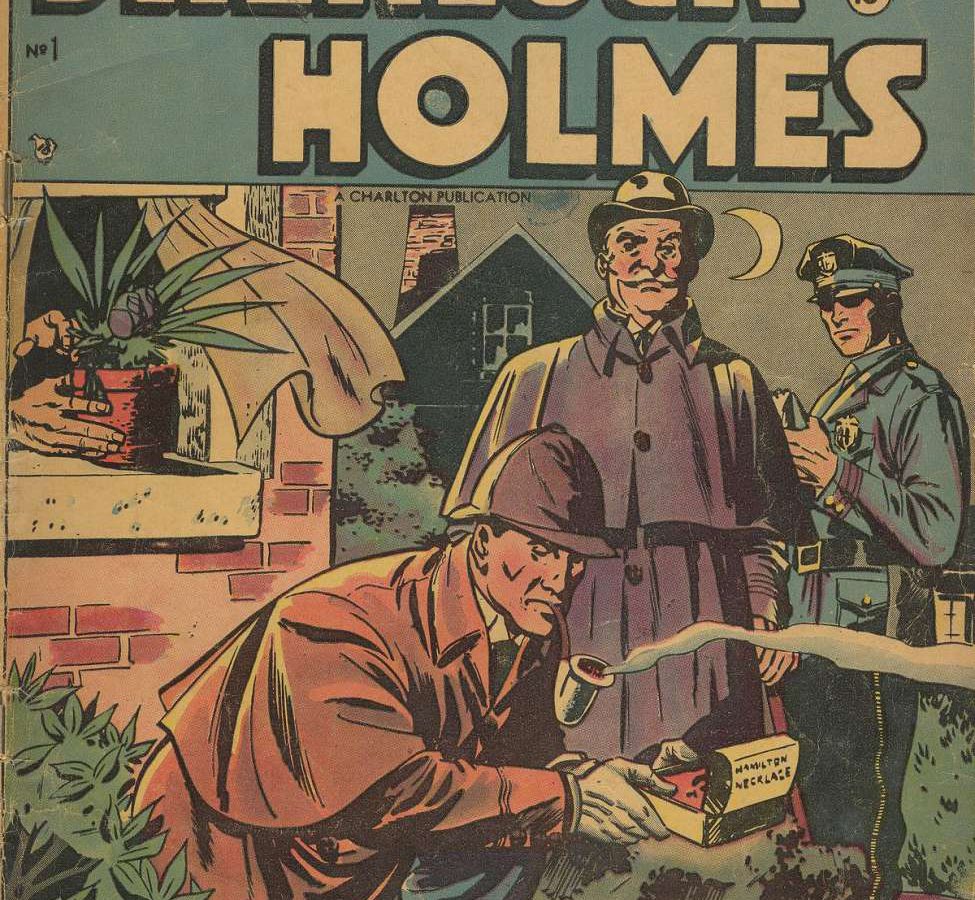

It’s a frequently recurring storyline in detective tales. A crime has been committed, and evidence has been found that appears to point in the direction of one of the characters, Mr J. Detective A – the ‘bad’ detective – sees the evidence and immediately concludes Mr J is guilty, arrests him and throws him into a prison cell. Detective B – the ‘good’ detective – is unconvinced of Mr J’s guilt, and pursues the problem until he discovers new evidence or facts that shed a completely new light on the original evidence, thus proving Mr J’s innocence and catching the real criminal.

In such stories, it’s always perfectly clear to us, as the viewer, who the good detective is. But in real life, the distinction is not so clear. Having always prided myself on my objective, analytical approach, it was a nasty shock for me to realise that I had been playing the bad detective for most of my life.

It was my coach who brought this fact home to me, although it took a long time for me to accept it. Feeling completely down about myself, I was sure that I was a failure. She suggested that this was a perception in my own head. I drew on my prized objectivity and cited several pieces of evidence that I was, indeed, a failure. My coach said that I could choose how to look at these things, and select the interpretation that would help me to feel better. My whole being revolted against this. How ridiculous, and childish, to create your own make-believe world so that you would feel better! Then, my coach explained RET – Rational Emotive Therapy – to me.

I am not going to discuss RET in detail in this blog, as I am certainly no expert. There are excellent professional sources that describe the steps involved in RET, and how they can be applied. Instead, I am going to write about the way I understand it, and how it has helped me.

In the past, whenever I’ve felt bad, I’ve blamed it on the situation. I had failed my driving test, faced an angry client, been ignored by my children when I told them it was time to stop playing and go to school. That made me feel bad. That felt entirely natural, and it made handling the bad feeling very simple – I had to change the situation. Pass my driving test, please the client, make my children listen. If the situation couldn’t be changed, then I was stuck with the bad feeling – with an extra dollop on top because I had failed to make it better.

In fact, the situation itself often has very little to do with your feelings. Picture the situation where a dog runs around the corner into the garden. My older daughter will be delighted, my younger daughter terrified, and I will be angry. Same situation, different emotions. Why? Because that direct link from situation to emotions is not direct at all. How you feel has a great deal to do with your own history, your predispositions and the assumptions you make. My older daughter would be happy to see the dog as she would love to have a pet – her positive predisposition means she sees a playful companion. My younger daughter would be terrified as she was attacked by a dog when she was little – her personal history makes her think the dog is coming to bite her. I would be angry, as my assumption would be that the dog is running loose because its owner hasn’t taken proper care. We would each create our own story around the incident, and that would determine how we felt.

RET helps you to recognize the assumptions and prejudices that decide how you interpret a situation. In recognizing them, you can question their validity. It is then possible to consider alternative interpretations. This is precisely what the good detective does, keeping an open mind and examining the evidence. For example, when I started my current job, I met two new colleagues in the hallway, and we introduced ourselves. As I walked away, I heard them laughing behind me. My immediate reaction was to feel self-conscious and awkward. Applying RET, I could recognize that I felt that way because my story about the situation was that I had done something odd, and so they were laughing at me. That story had its roots in my childhood, when other children regularly said nasty things behind my back. I was now in a completely new environment, so was it reasonable to assume this sort of thing was still going on? Was there an alternative story I could tell, if I let go of this assumption? Yes – their laughter could have nothing to do with me at all, perhaps one of them had just told a joke.

Which scenario was more likely? It was impossible to say. But believing the second interpretation – even just admitting its possibility – made me feel much better. More importantly, it affected my behaviour. Believing my initial interpretation would have made me shy and withdrawn, not the best thing when starting a new job. Believing the second interpretation allowed me to keep going out and making contact with new colleagues. Even in the case where my initial assumption was correct, and I had done something so odd that these two colleagues were laughing at me, this outcome was far better for me.

This was what my coach was trying to explain to me. She wasn’t suggesting that I should make up my own world – she was pointing out that I was already doing that. I wasn’t looking objectively at the facts at all, I was weaving my own story around them, determined by my present state of mind and my previous experiences, and then treating that as factual truth. Tracing back how I had constructed this sad story, I could see that there were many assumptions I was making that really didn’t stand up to the light of day. So, wasn’t it time to take those same facts and try to tell a happier story?

For me, RET has had two big benefits. The first is to apply a brake to my negative feelings. Something happens, I feel bad, and I think – wait a moment. Why do I feel bad? What story am I making up? Is it a reasonable story? Are there alternatives? Sometimes, as with the laughing colleagues, I realise a situation might not have been bad at all – it really could have been all in my head. Other times, I see that the situation was bad, but that I was making it far worse. Take the example of my children refusing to do what I was telling them. Any way you slice it, that is a frustrating situation. But add a good dollop of insecurity about my parenting skills, and it turned into confirmation that I was a failure as a mother. Being able to throttle that back and simply think, ‘there go the kids again, grrr, aren’t they difficult today?’, is a huge relief – and makes it easier for me to stay calm and think about the best way to handle them.

The second benefit is to understand that everyone else is also constructing their own story for the situation. If you see situations as being directly linked to feelings, then by definition everyone is going to have the same feeling about the same situation. If they don’t respond as you expect, then that is incomprehensible, and must be due to something wrong with either you or them. Take, for example, the situation at work that there is no clear project plan. For me, that sets off all kinds of alarm bells. How do we know who is doing what? How do we judge if we’re making enough progress? How can we decide in time if we need to change our approach? So, when I see that my colleagues don’t take any action to sort out the project plan, I get seriously angry. They are lazy, or stupid, or they don’t care about the success of the project. But, if I understand that other people view the situation differently, another interpretation arises. For many creative people, the lack of a project plan is heaven! They are free to follow their muse wherever it takes them. They are not being lazy, or stupid, or uncaring. Quite the opposite, they are passionate about what they do, and from their perspective, this is the best way of succeeding. It is like the famous dress illusion. I see it as white and gold. Others see it as blue and black. For both sides, it is inconceivable that it can be seen any other way. But it is all down to the assumptions that the brain makes.

Being aware of this doesn’t solve everything, of course. In the example I gave, my colleagues and I were working on the same project, so we couldn’t each go our own way, we had to choose a common approach. But seeing the different points of view shifts the problem from a fight over who is right and who is wrong, to a puzzle we need to solve together – ‘I need plans, you need creative freedom. How can we organize the work so we include a bit of both?’.

Sometimes, a situation is truly terrible. No incorrect assumptions made, no alternative explanations possible. Situations like that must either be changed or escaped from. I have no patience for those who refuse to solve real problems and suggest instead that anyone in difficulties should adjust their thinking to cope with it. But I’ve found that if I behave like a good detective and challenge my assumptions, then it’s amazing how many mountains turn into molehills. Elementary, dear Watson.