Perfection: The negative perfectionist

We live in a world where, increasingly, we expect perfection. Perhaps we don’t always admit that to ourselves, but it is evident in our behaviour when things go wrong. The smartphone that breaks, the train that is delayed, our child’s poor test scores, the outbreak of a virus. When these things happen, the predominant tendency is to cast around to find the person responsible, then complain, protest or sue to obtain an apology, compensation and – most of all – a promise that it will never happen again. New regulations, better technology, improved education, more effort, more money. If we only apply enough of these, then nothing need ever go wrong again. When improvements fail to materialise, we look elsewhere for perfection. Switch suppliers, move to another country, find a new partner. This constant quest for perfection is so ingrained in our society that we rarely even notice it, let alone challenge it. This series of posts will look at the effect of our desire for perfection on various aspects of our lives. This post: the negative perfectionist

My mother was a perfectionist, and worked tirelessly to make everything perfect – home, food, work, family life. She cooked delicious meals, made picture-perfect birthday cakes and gingerbread houses, sewed beautiful clothes for us – all while working at her job with so much dedication that, despite lacking the relevant academic background, she was made an honorary member of a medical association. Total perfection is never attainable, though, and every small setback hit her hard. A minor problem in the kitchen would be met with a howl of ‘Dinner is RUINED!’, and when one Christmas morning the patio doors had been left unlocked, so that rain blew in and dampened the rugs, she burst into tears.

My sister inherited that drive for perfection. Whether because I was the second child, naturally more reticent or simply lazier, I did not. I am quite content to buy Christmas dinner rather than slave for hours in the kitchen, to allow my shelves to accumulate dust, and to shut down my laptop at 5pm. What I did absorb, however, was a horror of failing to meet other’s expectations. At home, I hated the exasperated sigh when I didn’t follow my mother’s instructions properly in the kitchen; at school, I dreaded the strident tones of the teacher if I forgot my homework, or the mocking laughter of my friends if I messed up my class presentation. So, growing up, I did all I could to avoid things going wrong: planning ahead, thinking through all possible scenarios, doublechecking everything. I was so risk-averse that I carried my school blazer with me in my bag all through the summer months, just in case I had misunderstood the rules and got shouted at by a teacher. When things went wrong in spite of all my efforts, I would often lie to conceal the fact. As an adult, I was comfortable with my shop-bought festive dinners and dusty shelves only because, usually, no one criticised me for them. But when my family came to visit, the mere thought of their disapproving looks gnawed at me for days in advance, sending me to get out my cookbooks and vacuum cleaner.

Just like my mother and sister, I went to great lengths to avoid things going wrong, yet I never regarded myself as a perfectionist. Now, though, I believe there are two sides of the coin for perfectionism. Some people strive for perfection out of a longing to achieve the very best that they can. Others strive for perfection out of fear of what happens when things go wrong. They are terrified of the consequences of a misstep and, even more so, of the reactions of other people to their ‘failure’. I belong to that second group. I regularly have nightmares in which something terrible has happened and it is all my fault – or that I am being blamed for it. I don’t strive to achieve my potential, rather I strive to avoid messing up, and will limit myself to safe arenas where I can be sure of succeeding, rather than taking on a new challenge.

Both types of perfectionism, if unchecked, are exhausting both for the perfectionist and those around them. But the first group is at least spurred on by positive feelings, attracted by the vision of an ideal and a belief in their ability to achieve it. The second group is hounded by negative thoughts, constantly afraid of failure and rejection. A positive perfectionist offers to decorate the school for Christmas because they know they will do a great job of it (probably much better than any of the other parents). A negative perfectionist offers to do it because they fear being seen as antisocial otherwise – then expends great effort to avoid being ‘the mother who did the crappy decorations’. A positive perfectionist works hard in their job to achieve promotion, a negative perfectionist works hard because they are afraid they will be sacked. At the scene of an accident, a positive perfectionist will plunge in to take charge, while the negative perfectionist, despite desperately wanting to help, will hang back in fear of making things worse. In short, the positive perfectionist pursues opportunities, the negative perfectionist runs from risks.

Where does negative perfectionism come from? As children, we burst into tears or throw a fit of rage when things go wrong, but we don’t feel guilty or ashamed. We only think about our own feelings of frustration at being thwarted in our endeavours, or our bewildered hurt at being told off. Not about the consequences our actions had or the possibility that we were at fault. Then, over the years, the shell of oblivion starts to crack. Punishment from our parents or teachers ceases to be perceived as an incomprehensible act of meanness and starts to induce prickles of shame. Then the necessity of punishment becomes less, as the critical voice takes up residence in our own heads. The knowledge that we have hurt our friend’s feelings produces an echo of pain in ourselves, the realization that our actions have created trouble for someone else causes our insides to twist with guilt. So, we learn to police our own behaviour, to avoid causing problems or upsetting people. This is an essential process, otherwise the world would be populated with over-grown toddlers snatching all the toys and breaking them. But in negative perfectionists, somehow, that sensitization to the needs and expectations of others goes into overdrive.

At the heart of negative perfectionism is a deep-rooted feeling of inferiority and insecurity. The negative perfectionist feels that everyone else is better than they are, so they can only have a place in the group if they earn it, over and over again, by helping, impressing or pleasing those around them. None of us likes being told off for making a mistake, or criticized for under-performing. But for a negative perfectionist, this weighs far more heavily, as it might mean that others are discovering what they themselves already know at heart to be the truth – that they are simply not good enough.

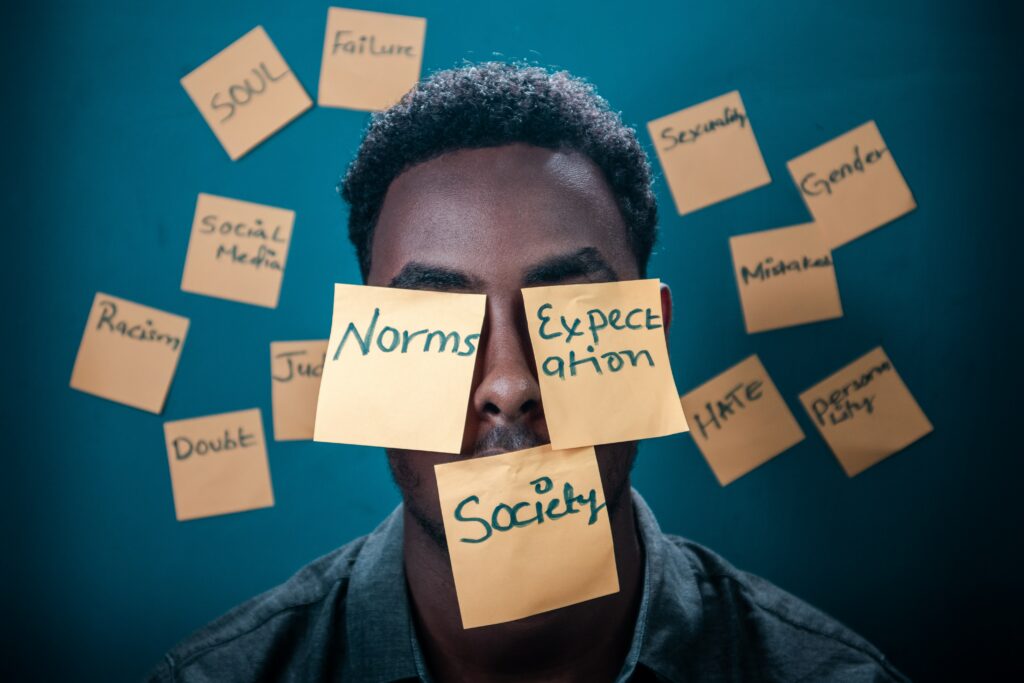

As a child, negative perfectionism is relatively easy to handle. Just do as you are told so your parents and teachers won’t get angry, and go along with your friends to keep them happy. Growing up, things get more confused – and confusing. What we need to do to stay ‘in’ with our teenage friends is rarely the same behaviour needed to please our parents. Authority figures turn out to disagree with each other, and we discover that there are plenty of people in authority whose values we don’t agree with at all. Reaching adulthood, we step into the wider world and discover an infinite array of opinions about what is right and wrong. It is impossible to do the ‘right’ thing all the time, as the same action that is praised by one person is deplored by another, so incurring displeasure is unavoidable.

At the same time, our circle of concern grows. We end up juggling career, parents, partner, children, friends, hobbies, social responsibility. Just as there is an infinite range of opinions, there is also an infinite range of important issues demanding our time and attention. It is impossible to tackle them all. A negative perfectionist, while understanding this rationally, retains a deep sense of guilt about their neglect of each thing that they don’t do. Every request for help from the children’s school, every call for volunteers to organize the work outing, every impassioned plea for action in the media that they don’t act on is another stone added to their burden of guilt, their sense of not doing – or being – enough. Under the pressure of this load, any dreams and ambitions that don’t happen to benefit the group are quietly pushed to the background (most likely they would have failed, anyway).

If you haven’t experienced this yourself, it may sound ludicrous. But negative perfectionism, at its worst, is like trying to navigate a narrow, rickety bridge over a lake of boiling lava, while people shout conflicting advice as to which way you should go. For a long time, that terrible paradox of the absolute necessity of pleasing everyone and the absolute impossibility of doing so turned my life into one long enervating tightrope act, and I think I am far from being the only one to experience this.

What can help in combating negative perfectionism is to reach back to early childhood, to that blind belief that we belong, that our parents love us no matter what we do. As adults, we reject that as naïve. But it holds a fundamental truth. We are all imperfect beings, yet we all have the right to be here. None of us asked to be born – but then, none of us needed permission to be born. We don’t earn the right to exist in this world, it is ours as our birthright. Whether we are incredibly successful in all we do, or whether we are continually screwing up, we have our place, and no one can cast us out of it.

It is also important to realise that we are not so inferior as we believe. Take a moment to think about the people around you that you admire, the people whose talents you envy. What are the downsides of those talents that cause problems for you or others? Perhaps it’s the creative, artistic friend who is never on time when you meet up. The genius at work who is so busy achieving breakthroughs that they are oblivious to the team member on the edge of burn-out. Or the loving parent whose continual interference in your own parenting decisions drives you up the wall.

Then, take another moment to think about your own weak points, and discover their upsides. The shy introversion that makes you a great listener. The insensitivity to social conventions which means that you are the person everyone secretly relies on to say what they are all thinking. Even – yes – the excessive fear of failure that means you are always so well prepared. Each of us is a complete package, with our own unique combination of strengths and weaknesses. In this respect, we are all equally imperfect. Where someone outstrips us in one respect, they fall short in another. No one gets to cherry-pick only the good bits – yet far too often when comparing ourselves with others, that is exactly what we do.

Finally, imperfections are not an unfortunate side-effect of being human. Imperfections are the essential glue that holds us humans together. A perfect individual requires no one – and perfectionists are notoriously bad delegators. They wear themselves out, while leaving no room for others to contribute or to learn something new. Perfection is a protective armour – but armour keeps people at a distance. Admitting we can’t do something, admitting we are human, allows others in. Even better, it gives them the opportunity to help us in an area where we are weak but they are strong, making them feel needed and valued. When we are all honest about our strengths and weaknesses, we know who to ask for help, and to whom we can offer our own help in return, who we can learn from, and who we can teach. We lift each other up instead of tearing each other down.

I am never going to casually brush it aside when I do something wrong. Nor will I ever lose my sense of guilt for all the good things I leave undone. However, regularly repeating to myself that we are all imperfect, that we nonetheless have an equal right to exist, and that imperfection can actually be a good thing, brings an overwhelming sense of relief, a welcome rush of fresh air into the lungs. Other people’s criticism, disappointment, anger and blame still wound me, but I can see that they are an inevitable consequence of a complicated world. They can be valuable observations, or they can be based on misunderstandings, the person’s own insecurities, even a simple difference in outlook. As such, they are not divine judgements upon me, but just one factor among the many that I need to consider when making decisions. I can accept that I can’t do everything, because as long as I do my small part, then that is enough, because there are others who will do theirs. I can allow myself the space to follow my dreams, useless as they are to anyone but me, even dare to stop re-reading and editing my blog post and just post it anyway, imperfect as it is.

There is not one single perfect person in this world. Yet there are so many imperfect people that I love deeply and could never do without, even though their faults sometimes infuriate me. Perhaps, one day, I can accept that the feeling may be mutual, that – warts and all – I belong.