Follow the rules or follow your own judgement?

Ever since our daughters reached the age at which they could reasonably be expected to take some responsibility for their actions, my partner and I have been painstakingly trying to teach them to obey rules. Don’t run with scissors, don’t take slime to school when the teacher has banned it in class, always tell Mummy and Daddy where you are going, don’t sneak into the kitchen to steal Mummy and Daddy’s chocolate (that last one is still a struggle). In the beginning, the rules seemed to disappear into their minds like stones lost in deep water, barely causing a ripple. Later, surprisingly, they re-emerged. Not to be followed, you understand, but to allow my daughters to assume the role of police officer, gleefully pointing out any infractions committed by others. As they grew older, they also became keen lawyers, noting every temporary relaxation in the rules for later use against us as precedent. ‘But yesterday’, (in reality, three months previously), ‘we were allowed a biscuit AND sweets’. More recently, they have taken to pouncing on any differences between our rules and those at school and daycare. Their main aim in all of this is, of course, to get their own way, and the need to constantly defend our decisions sometimes drives both my partner and I up the wall. But there is another reason behind their continual challenging of the rules. They are trying to grasp how the world works, and understanding the rules is an important step in this.

Tiring as this has all been, the worst is yet to come. Because wherever there are rules, there are exceptions. You don’t tell tales to the teacher – except when someone is doing something dangerous. You don’t tell lies – but you don’t tell your friend how stupid they look in their new jumper, either. As my daughters develop from children to young adults, they will increasingly be faced with the choice of when to follow the rules and when to break them. I wish I could present them with an easy way of making such choices, a ten-step yes/no decision tree that always comes out at the right answer. But in reality, it’s a struggle we all face.

As a child, I dreaded being told off, so I followed the rules scrupulously. One of the first things I noticed was that the rules were applied unevenly. If I talked during assembly, then I was immediately told off. Whereas the black sheep of the class could go quite far before he was called back into line. Next, I realized that while following the rules won me the praise of the teachers, my classmates disliked me for being a ‘goody-goody’. Becoming a teenager, I came to understand that most of the teachers actually also shared this opinion.

In society in general, we prefer rebels. Those who follow the rules are dull and boring. And those who enforce the rules are out to spoil our fun and make our lives difficult. The park attendant who throws us out of the park for holding a barbecue, the neighbours who complain about noise after 11pm, the traffic warden giving us a ticket when we only parked for a moment to get our children to school.

This attitude is switched around once we are the injured party. When our local park has been burned down by a careless group having a barbecue, when someone keeps us awake by having a noisy house party into the early hours, when we can’t park on our own street because it’s filled with parents parking for the nearby school. How we feel about rules tends to depend on how those rules benefit or disadvantage us, as satirized in an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm:

Larry David: Whoa, I don’t understand, what’s going on here? I came in before her, I signed in the sheet.

IMDB: The ‘me first policy’ of Larry David

Nurse: Well, you’ll be happy to know they’ve changed policy.

Larry David: Changed policies…?

Nurse: Now we see people on the basis of their appointment time and not their arrival time.

Larry David: But that’s ridiculous. One person complains and all of a sudden everything gets changed?

Nurse: This was based on your idea the other day.

Larry David: I know, but what are you listening to me for? I don’t know what I’m talking about. Nobody ever listens to me.

Nurse: So apparently, it’s not about the policy at all. It’s more about you going first?

Larry David: Exactly!

Nurse: So if you go first, whatever policy… .

Larry David: That’s a good policy, “me first”, that’s the policy.

Our shifting attitude to rules isn’t helped by the fact that it is impossible to come up with a set of rules that are entirely unambiguous and define an appropriate response for every possible eventuality. Sometimes, rules even come into conflict with common sense. Who hasn’t been faced with a ‘jobsworth’ who insisted a child could only bring hand baggage on the plane if they carried the bag themselves, or who refused to sell alcohol to a pensioner because they couldn’t produce proof of being over 18. Most of us accept that you need a healthy dose of common sense to interpret the rules appropriately and – where necessary, to bend or even ignore them.

Using our own common sense allows us to compensate for the gaps and inadequacies of the rules. But it also leaves room for bias to creep in. When deciding whether to commit – or ignore – an infraction of the rules, we weigh up whether there is a good reason for the infraction and whether anyone is really hurt or inconvenienced by it. This depends on our perceptions of what a good reason is, and what constitutes hurt or inconvenience. And those perceptions are influenced by our own experience and prejudices. Take someone who parks in the ambulance-only zone. They may do so to get their critically ill partner to A&E, to drop off their child who is nearly late for their clinic appointment, or to bring their friend to an interview for their dream job as medical specialist. Depending on whether you yourself are a parent, whether you are someone who does their best to be punctual or who also regularly arrives too late, and how highly you value a career, you will find each of these a good or bad reason. And you are also influenced in how you assess the inconvenience of briefly blocking the ambulance bay – how long is ‘brief’, how high is the chance of an ambulance arriving, are you an ambulance driver who was once blocked while ferrying a critically ill patient…?

When a UK woman admitted – unrepentantly – to being a Soviet spy, it should have been an open and shut case. Instead, a furious debate erupted over whether to prosecute. Because she was 87 years old, and frail, and someone’s granny. For some, these facts were sufficient reason to put the rules to one side, for others, they were totally irrelevant. Leaving decisions up to our own individual judgement produces a huge variation in outcomes. In particular when you factor in that we are often tempted to pay more attention to our own desires than to our conscience. It is impossible to ensure fairness and consistency when we each judge for ourselves.

The situation becomes even more complicated when it is not only the interpretation of a rule in a specific situation that is debatable, but the law itself. Abortion, prohibition, homosexuality, prostitution, these are all highly controversial topics with ditto laws. There are laws from the past that some of us now regard with horror; there are recent laws that convince other groups that the country is going to the dogs. Citizens are expected to follow the law, yet laws are also expected to change to adapt to our evolving society. Changes must always be preceded by citizens challenging the law. And as there is only one set of laws for a country, there will always be groups or individuals whose conscience dictates a different code of behaviour than the official laws. When is it right to follow the law, when is it right to challenge it? We will all answer differently, depending on our own convictions.

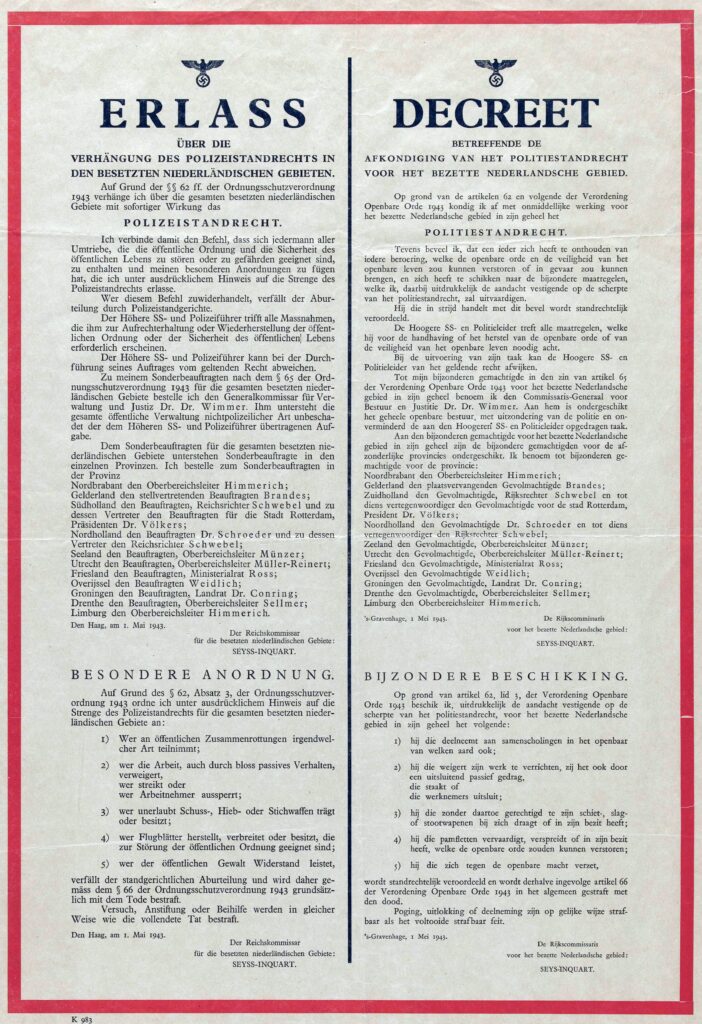

NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

Finally, those in charge of making the laws and enforcing them can themselves be dubious. Prior to 10th May 1940, a good Dutch citizen followed the law. After that date, it was those who followed their own conscience and defied the laws made by the Nazi occupiers – even stealing and killing – who later became the heroes of the resistance. On the other hand, the Baader-Meinhof group, who also followed their conscience to defy a government they saw as influenced by Nazi ideology, were regarded as terrorists for stealing and killing. The classification hinges on whether you perceive the authorities to be good or bad. Obedience to authority is therefore not automatically a virtue, yet we are all brought up to do it. The infamous Milgram experiment showed how perfectly normal people were willing to administer potentially lethal electric shocks to another person when instructed to do so by an authority figure.

So, should we follow rules, or trust our own judgement?

It’s time to declare my colours here. I am a fan of clear rules, and I think they should be followed and enforced. I believe it’s fairer, it bolsters our own consciences, and it saves a lot of time and confusion. But I have also experienced plenty of situations where rules just plain got in the way of common sense. For example, being denied access to a bar in America at the age of thirty-three while my two-year-old was permitted to enter, or having to hire a tow truck to take my car to the test station in Belgium, because I couldn’t drive it without insurance – and I couldn’t get insurance without the car being tested. Fortunately, these situations were only annoying, but I’ve heard plenty of examples of where illogical rules can ruin people’s lives, such as Dutch citizens losing their bank accounts because, according to bureaucracy, they are US citizens. So, I’m also a believer in a good dollop of pragmatism when the rules fall short.

The recent corona crisis, however, has fascinated me in how it lays bare the deficiencies of combining rules with relying on people’s own judgement. This has undoubtedly played out in other countries too, but as a foreigner living in the Netherlands, I find it particularly interesting to speculate on how the particular culture and system of government here has affected the process.

In the Netherlands, great emphasis is laid on citizens using their own judgement and taking responsibility for themselves. The police have a cautious approach, preferring to give verbal warnings rather than fines, and fines rather than prison sentences. Frequently, authorities make the decision not to intervene, to avoid a potential escalation of the situation. This is even enshrined in government policy, in the concept of ‘gedoogbeleid’, in which there is a deliberate decision not to enforce certain laws. The most well-known example is the policy on soft drugs, where so-called ‘coffee shops’ are allowed to trade in small amounts even though the drugs are illegal. This is done for pragmatic reasons, as the trade is seen as inevitable, so it is regarded as better to have it under some measure of control rather than to have it continue underground. Soft drugs are officially tolerated, while officially still being illegal.

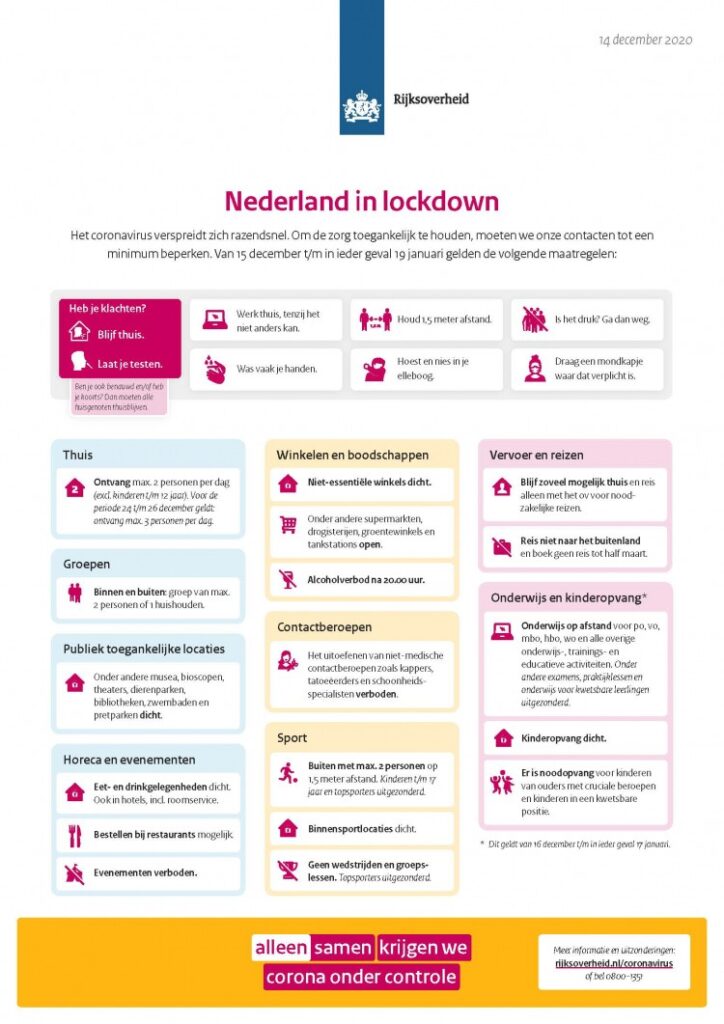

At time of writing, the Netherlands is slowly emerging from what the Prime Minister announced in December 2020 as ‘a strict lockdown’ (as opposed to the ‘intelligent lockdown’ of the first wave in Spring 2020). The measures were indeed strict – non-essential shops, restaurants, schools and daycare all shut, and later on also an evening curfew. Regular surveys by the RIVM (the institute for Public Health) have mostly shown a great deal of support for – and compliance with – the rules. Yet the numbers of infections stayed high for a long time. How could this be? Perhaps the rules were not effective in combating infection. But I would also suggest, based on my personal experience, that the rules were often simply not being followed.

Did all those people answering the questionnaire lie, then? I don’t think so. I think they all believed that they were following the rules. But, in true Dutch style, they were using their own judgement to interpret them. I saw this time and time again in my own friends and colleagues. They visited their families, went on weekend trips with friends or organized games evenings. These were all against the rules, yet they were always at pains to emphasize the precautions they had taken – self-isolating for a week beforehand, not hugging, keeping the windows open. They might not be keeping to the letter of the rules, but, in their eyes, they were keeping to the spirit. Given the huge negative impact of the rules on people’s lives, the temptation to use your own judgement in a way that mitigates that damage while still feeling safe is hard to resist.

Other rules, such as ‘work from home where possible’ were extremely easy to follow because ‘possible’ is such a vague term. What if you could work from home, but doing so would adversely affect your work, because there is noise from building work, because meetings are less effective over a zoom link, or because the isolation is affecting you psychologically? Is it ‘possible’ then, or not? What if your employer insists you come in to work, and you fear losing your job if you refuse? Employers and employees chose their own definition of ‘possible’, and as far as I am aware, no one from the authorities ever went to check up on the validity of the choice. The prime minister relied on people taking their own responsibility. He later admitted that this was a mistake.

Further, there was a whole group of people whose own judgement told them that they should not follow the corona rules at all; whether they believed corona was a conspiracy, that the rules were ineffective to combat infection, or that passing on the virus was the best way to defeat it by building up herd immunity. These people were unlikely to have responded to the RIVM questionnaire. Instead, they protested, or distributed leaflets supporting their own point of view. No careless rule-breakers, but people thinking for themselves and following their conscience – as historically encouraged in the Netherlands.

Working out clear rules for the corona crisis has not really been a great success either. This is not so surprising, given it was a novel situation and the expert advice was constantly changing. Legal experts spend years hammering out inconsistencies and ambiguities in laws, now the rules had to be thrown together from one day to the next. While the basic rules were clear – keep your distance, wash your hands – the devil was in the detail, as I described in a previous post. The individual implementations of the rules were inconsistent and conflicting, producing absurdities such as that my children could play football outdoors if a football club organized it, but not if their Scout group did, or that it was fine for my mother-in-law to visit us, but not for us to visit her.

Consistent enforcement of the rules was never going to be possible either, realistically speaking. You can’t police 17 million people at the same time. But the traditional pragmatic response of the Dutch police has led to a jaw-dropping disparity in enforcement, with police deciding not to stop 12,000 football fans celebrating their team’s victory, while they did break up a party of 30 people the day before, and had fined a group of four for eating cake together outdoors in 2020. To add insult to injury, the health minister praised the police for the restraint they showed towards the football supporters, while insinuating that the entire country might have to wait longer for relaxations in the rules as a result of the supporters’ actions.

Finally, the authorities regularly implore the public not to ‘push the borders of the rules’. In other words, not to do things that are, strictly speaking, permitted, but that might be risky. Once again, it is left up to the individual citizen’s own judgement to decide where the invisible border zone of the rules begins. As always, our own judgement depends on how we assess the risks versus the benefits – how important do we find it to meet up with other people? How risky do we believe it is to have a guest visiting at home? And, as always, our own judgement is coloured by our experiences and prejudices. A group of elderly people chatting together in the park, standing perhaps a touch too close together, is unlikely to draw criticism. A group of teenagers doing the same, with music and bottles of beer, will probably provoke scandalized reactions about how irresponsible their behaviour is.

In the case of coronavirus, I believe that the combination of rules and own interpretations has severely hampered an effective response to the crisis. We are caught in a cycle in which rules are issued, people interpret them in their own way, the rules are not fairly enforced, and so everyone does their own thing. When infection numbers rise the efficacy of the existing rules is not reviewed; instead new, stricter rules are introduced, and the cycle starts again. Those who lose out most are those who do faithfully follow the rules, the best behaved children in the class who didn’t talk while the teacher was out of the room but who still got put in detention along with the rest of the class.

I dread having to teach my children to navigate the murky waters of rules. Where there is a time to obey and a time to rebel, but no rule to help you to distinguish the one from the other. All I can do is to talk these situations over with them as they arise, give them my perspective, and try to assist them in forming their own conscience. To impress upon them the necessity of balancing their own needs and desires with respect for the rules and consideration for the consequences of their actions, for themselves and others.

However, there is one rule that is forever set in stone: