Hollywood Frogs – The Hero

Films are not reality, we all know that. Yet influences from films sneak into our minds without us realising it, skewing how we look at the world. This series examines some of these ‘Hollywood Frogs‘. This post: The hero.

Hollywood films revolve around the hero. We identify with them, and usually wish we could be them. Heroes in Hollywood are mostly male, white, and attractive. While any of these points are worthy of an entire blog post on their own, they are a reflection of the biases society has in general, rather than a peculiarity of the film world. Hollywood makes many particular choices regarding its heroes that derive both from the limitations of film as a medium, and from its own raison d’être – to make money by producing popular blockbusters.

These choices mean that I never see a film hero in whom I can recognize myself. While that may seem trivial, when I think of the ways in which I most feel like a failure, I find I can trace them back to certain characteristics that Hollywood heroes inevitably have – and that I do not. Somehow, it seems, I end up measuring myself against these fictional heroes, and of course I fall short.

Heroes are dynamic

Heroes take action. It’s not for nothing that we talk about ‘action heroes’. For many film leads, it’s inherent in their onscreen occupation – superheroes, spies, soldiers, police officers. But even the ‘ordinary’ leads tend towards doing. Going on a quest for pirate treasure, joining a revolutionary group, travelling through space to battle an alien menace. They may do it reluctantly, but they still do it. It’s a good job too – imagine The Goonies where the kids stayed home to help pack for the move, The Life of Brian where Brian doesn’t join the People’s Front of Judea but cleans up his room, or Aliens where Ripley decides to endure nightmares in her tiny, grubby flat rather than return to face the real terror.

Heroes who take time to observe and reflect, or delegate action to others, are not Hollywood material. In Margaret Atwood’s novel ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’, the hero, Offred, is largely passive, overwhelmed by the dictatorship around her, whereas in the 1990 film version she kills her oppressor, and in the recent TV series she ends up running an entire revolution. In Paddington, the loving, nervous, overprotective father is seen as boring, and only becomes a hero once he recklessly climbs out of a window on a mission to rescue Paddington, at which point his face is quite literally filled in as a hero in his wife’s imagination. Hollywood heroes don’t stay on the sidelines, they don’t hesitate or worry, or decide that it is best to do nothing. After all, a thrilling, brilliantly choregraphed action scene is what cinema was made for, whereas a shot of someone carefully weighing up their options is likely to send the audience to sleep.

I am not someone who springs into action. I prefer to watch what is going on and think about it, to make a plan, to talk it over with someone else first. Compared to the heroic examples in films, I feel inadequate and dull as ditchwater.

Heroes always know exactly what to say

Picture a scene in a film. It is a critical moment. To save a town from a nuclear bomb/win over the woman of their dreams/trick the villain into confessing, the hero must hold an impassioned speech. Eloquently, with emotion – but always in control – they sway those present to their point of view. When a speech is not appropriate, they still come up with the consummate quip, and supposedly casual conversations are perfectly timed and filled with beautiful – and sometimes comic – prose (When Harry met Sally). Even characters who are supposed to be socially inept are never lost for words when the key moment comes. And children are just as articulate. Forget ‘children should be seen and not heard’ – the mouthier, the better, is the maxim for Hollywood.

Heroes always know exactly what to say. Well, of course they do. They are following a script, written, revised and polished by talented writers trained to create clever dialogue.

Once more, the more introvert heroes from literature fail to make the transition to the big screen. Take Fanny Price in Jane Austen’s classic novel, Mansfield Park, who received a Hollywood makeover for the film version:

Wikipedia

It’s understandable that Hollywood makes such choices. While books offer the unique possibility of looking inside someone’s head, films have to turn these thoughts into dialogue, or else be doomed to a perpetual voice-over. Introvert characters must therefore be forced out of their shells, to literally say what they think.

I am far more a Fanny Price in the novel version than the film one. I’m not up to rousing speeches or witty repartee – even a smart rejoinder usually escapes me until hours or even days later, when I think, ‘THAT’S what I should have said!’. I prefer to express myself via writing, which gives me time to think of what I want to say. Maybe some of those screen writers are just the same. But, on film, the written words they spend so much time honing are declaimed not only confidently, but off-hand, as if the words have just occurred to the person speaking them. Giving me the feeling that I am a dumb idiot when someone delivers a cutting remark and my mind simply goes blank.

Heroes don’t make mistakes

Think of the classic chase scene. The hero pursues the villain, never stopping, effortlessly negotiating every obstacle in their path. If their vehicle is destroyed, they swiftly transfer to a new one, whether that be a boat, car or bike, then are instantly back on the trail. If they take a detour, it magically turns out to join up with the villain’s route at precisely the right moment. Decisions are not only made instantly, they are also correct.

The same goes for escapes. Whether the threat is a crashing plane, an exploding bomb or a zombie horde, the hero always takes the right turning, kicks in the right door, leaps with the right timing to land on the moving vehicle. They trust or suspect the right people, ask the right questions, run in the right direction.

The classic horror film punishment for errors is a gruesome death, as is hilariously spoofed in Scary Movie. We shout at the screen: ‘Don’t do that!’. ’Don’t go there!’, then watch from between our fingers as another minor character bites the dust, secure in the knowledge that the hero will succeed where others have failed, because they won’t make such stupid mistakes.

Actually, heroes do sometimes make mistakes. But they are carefully selected mistakes intended to facilitate the plot. To show how human the hero is, to teach them a valuable lesson, to provide a dramatic downturn from which they can return triumphant. But, after the necessary agonising, they recover from their error. And from that point onwards, their judgement is perfect once more.

Or the character is a bumbler, constantly making mistakes, such as Johnny English, attempting to break into the enemy’s secret headquarters, only to get the wrong building and end up holding the bewildered patients of the neighbouring hospital at gunpoint, or Bridget Jones arriving at a garden party dressed as a playbunny. We warm to such characters, secure in a cosy complacence that we are at least not as bad as that. Yet even the bumblers ultimately do the right thing and achieve their perfect ending.

I literally have nightmares of being in some dramatic, film-like scenario – an erupting volcano, a zombie attack, a virus outbreak – and that I make all the wrong decisions. Everyday life for normal human beings is filled with mistakes. We forget our keys, miss the bus, lose vital documents. We choose the wrong career, the wrong partner, follow our heart when we should follow our head, and vice versa. Things don’t always turn out right in the end. But we don’t see this reflected in our entertainment. A hero who makes mistakes again and again, and yet is still an intelligent, respected, competent person, is largely absent in mainstream film.

Heroes do it alone

We adore lone heroes. James Bond, Spiderman, Ellen Ripley, Harry Potter. They may have friends, families, support teams back at headquarters. But at the crucial moment these get hit on the head, locked in another room, disabled by a communications failure, so that in the climactic stand-off the hero is alone. And they are equipped for that, being able to do anything that the situation requires, from athletic stunts, to mechanical (or actual) wizardry, to brilliant intellectual deductions. In ensemble films, there is always a leader, who fits the standard criteria for a hero, such as Danny Ocean in Ocean’s Eleven. In any case, lone heroes tend to be preferred over teams, to the extent that in ‘historical’ films Hollywood often ignores contributions from others in favour of attributing it all to their hero, as in The Imitation Game.

That’s a real shame, as a team offers non-heroic types like me the best chance to see ourselves in a film while still maintaining a visually exciting narrative. A team can be diverse, including different types of characters who aren’t required to drive the plot forwards by brilliant insights, brave leaps of action, stirring speeches. Characters who can make mistakes and then be helped by the others. In short – the characters can be much more realistically human.

However, even though the supporting members of an ensemble cast may be allowed to get away with not ticking every single one of the hero boxes, they each have a special skill that they contribute to the group, something that makes them unmissable. Which brings us on to the final essential characteristic of a Hollywood hero.

Heroes are special

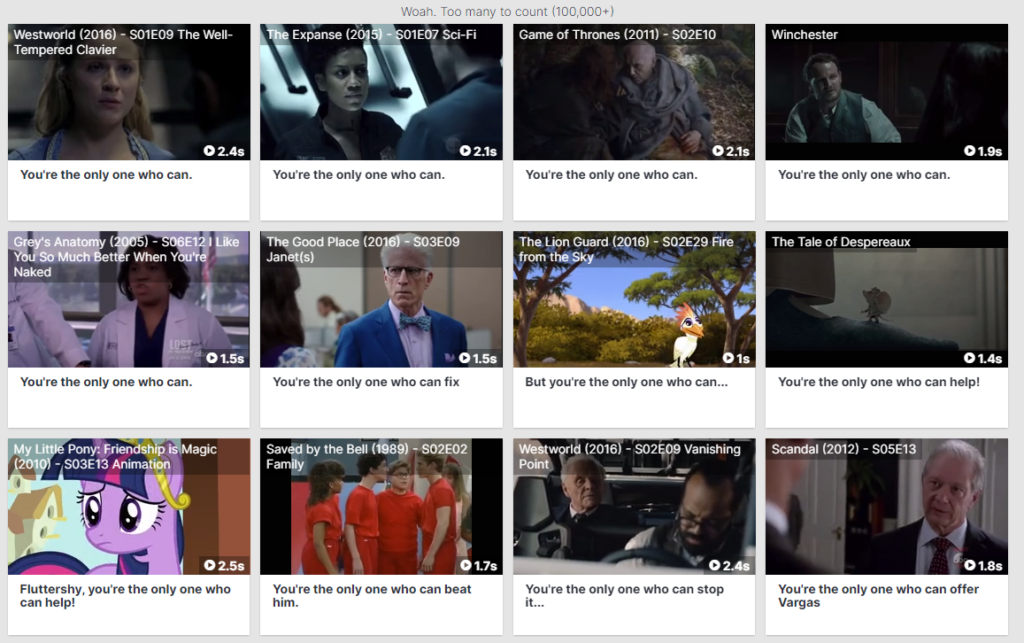

All heroes are special. They are an alien with superpowers, they are the heir to a kingdom and the only one who can free it from a curse, they are a world famous secret agent. If they start off as an average person, they will somehow be transformed: by a bite from a genetically engineered spider, by learning karate, by running a marathon to win back their ex. In the end, they are the only one who can do whatever it is that the film requires to be done.

It’s understandable that heroes aren’t just average people. After all, they have to be special to make a connection with us in the brief timeframe of a film. But the implicit message to the rest of us ordinary mortals is: if you don’t have a special talent, then you have no value. Perhaps that is part of the reason why we are so obsessed with film stars; we hope that somehow, some of that special star quality will rub off on us. We even have films that hold out precisely that hope: of meeting a film star and, through them falling in love with us, becoming special ourselves (Notting Hill).

Can I ever be a hero?

In real life, I don’t know anyone who comes remotely near meeting the criteria for a Hollywood hero. The most self-confident decision makers, the most silver-tongued speakers, the most obsessive perfectionists, the most independent trailblazers – they all fall far short of the Hollywood paragons. Such people don’t exist, any more than a normal person on the street has that ideal Hollywood beauty. Physical perfection onscreen is only achieved with makeup and airbrushing. Likewise, perfect competence onscreen is only achieved by scripts, stuntmen and camera trickery.

It shouldn’t matter that none of us can equal a Hollywood hero. Because the sole purpose of Hollywood heroes is to persuade us to spend our time and money on going to watch them in the cinema. Real life requires totally different skills. Quietly observing, listening instead of speaking, making mistakes and cooperating in teams may be cinematic dross, but they are essential parts of normal life. We don’t have to win over an audience in the space of two hours; we have our entire lives to build up relationships. We don’t have to be special to be loved – we are special to others because they love us.

I don’t think I will ever see someone resembling me as the hero of a film. But why does that bother me? I think it’s because I subconsciously equate Hollywood’s judgement with the judgement of society as a whole. If my qualities aren’t valued in films, then it follows that they aren’t valued by anyone. While Hollywood could definitely do more to expand its narrow representation, ultimately it is there to entertain, not to recognize each individual’s value. For my own validation, I should look to those close to me who are capable of appreciating what I do, not compare myself to fantasy figures created to sell big at the box office.

Next Hollywood Frog: The emotional moment.