Just Say No

It was the 1990s, on a campsite somewhere in the Alps. Golden evening light slanted through the trees, majestic mountains rose up in the distance. I stood in a field behind the rows of tents, a Celine Dion song drifting from a nearby radio, finally receiving my first kiss. This was a milestone I had not believed I would ever reach, being assured by both my classmates and my mirror that I was deeply unattractive. So, I was thrilled beyond belief that the handsome older boy I’d met that evening seemed to think otherwise. True, the kiss itself wasn’t really living up to my romantic fantasies – but at least I was being kissed.

Then, all of a sudden, his hand slid up the inside of my thigh. My response surprised both of us.

‘Non’, I said.

Gently – but firmly. ‘Non’, I repeated, backing away. He muttered something unintelligible and abruptly turned to go, stomping off into the night in a bad temper. Leaving me behind – a little regretful, but mostly proud and more than a little astounded at my own assertiveness.

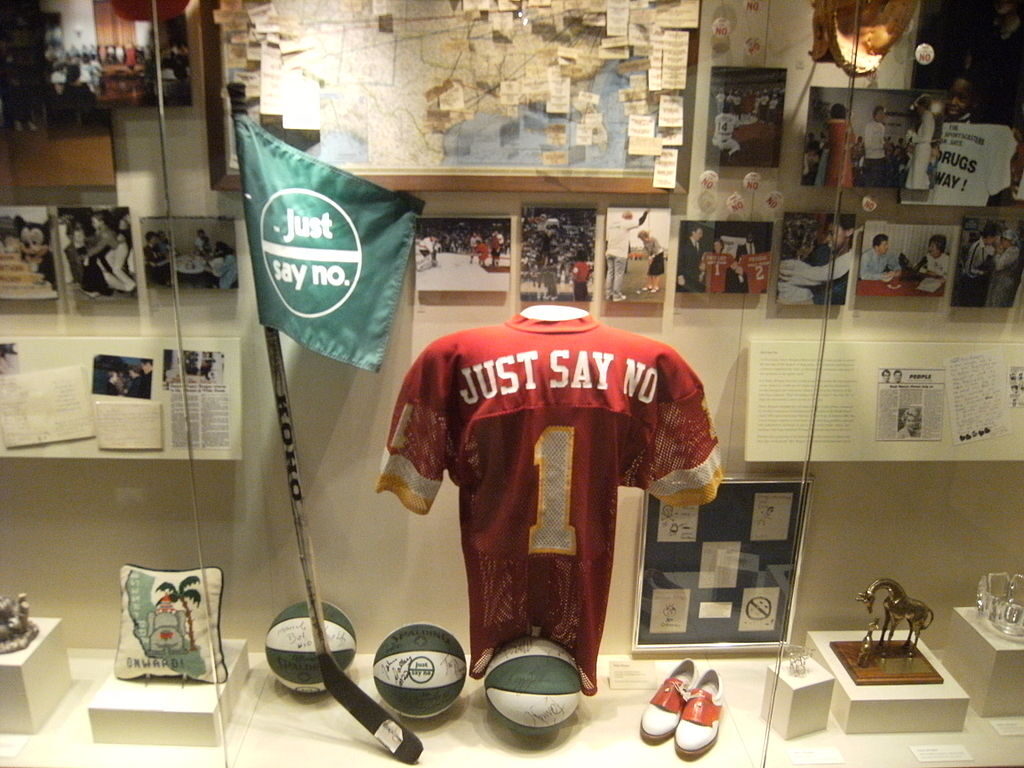

Anyone growing up in the UK or US in the ’80s and ’90s’ will instantly recognize the words ‘Just Say No’ from the famous anti-drug campaign. For me, they are forever associated with the cast of Grange Hill belting out the eponymous refrain to their hit anti-drugs song, in suitably sulky teenage style. The same mantra was later applied to sexual activity and relationships in general. It all seemed so simple. You aren’t interested in a date? You don’t want to have sex? Just Say No.

In reality, saying no is considerably more complicated, and I failed miserably to sustain the good start I’d made in that field in France. Travelling on a train as a student, I met a boy, and we chatted pleasantly until his station neared. At that moment, he asked for my number. I didn’t want to give it to him. He seemed nice enough, but I wasn’t interested in anything more. However, the very fact that he was a nice guy made it seem impossibly mean for me to say no. I handed over my number, and he duly commenced calling me. At around midnight, in most cases. Having no idea of how to handle this graciously, I simply blocked his number. What a cowardly way to escape the situation, and far more hurtful to the boy in question than if I had got up the courage to refuse his request in the first place.

As my final round of exams began at university, I received a very sweet, shy email from a friend I regularly sat with during lectures. He said how much he enjoyed spending time together, and asked if I would like to be more than just friends. I didn’t fancy that, and felt very bad about turning him down. But the distance imposed by email made it far easier to do so. Although, even then, I was unable to refuse with the simple, honest truth. Instead, I blamed my refusal on exam stress, and said I had no time for a relationship. My excuse may have salved my conscience and possibly softened the blow for him. But what if he had taken it at face value, and approached me again after the exams were over, all eager to start the relationship I had seemingly only deferred? Luckily, that didn’t happen – but I would have been in big trouble if it had.

During my first job, I attended a week-long training course, during which I became friends with another programmer. On saying goodbye, he suggested a hug. I was unwilling, but – once again – didn’t want to spoil the previously friendly atmosphere by saying no. He duly hugged me – then added a lingering kiss on the cheek, which was as unwelcome to me as that hand on the thigh so many years before. Yet the public location and the week-long history of friendly contact combined to make it seem impossible for me to make a fuss.

Was all this just a result of my poor social skills? I might have thought so, if I hadn’t happened to hear about a service that supplied cards with a special phone number to hand out instead of your own. Anyone ringing it heard a courteous recorded message to the effect that the person who had given them the phone number was not interested, but felt too bad to say ‘No’. Clearly, I wasn’t the only one struggling with this issue.

To find out how such behaviour is received by the other party, you only have to do a little googling. ‘Cowardly’, or ‘apathetic’, ‘don’t know what they’re looking for’, are among the politer reactions. I can completely understand the confusion and hurt, even the anger. As one man remarked, ‘What is mean about simply saying something like “I’m sorry, but I’m just not interested”?

Sometimes, of course, people in such situations feel threatened or coerced. There are very few human beings – male or female – who dare to say no when they think it may provoke aggression or – worse still – physical violence. That is absolutely no fault of theirs. The blame rests solely with the person intimidating them. And, don’t forget, the memory of such an incident, or even hearing about it second-hand, can already be enough to make it very hard to say no, even if there isn’t any immediate indication that the present person will react badly.

This has, fortunately, never been the case for me. My fear has never been for my safety. No, my fear has always been social. Saying no to someone who asks for my number, who gives me an unwanted kiss, who asks me on a date, feels so rude, so selfish, so antisocial. I shy away both from appearing to be a mean, egotistical person, and from causing someone else pain. But avoiding those bad feelings means either having to allow behaviour I don’t want, or causing the other person more pain at a later date when they realise my deception. Isn’t saying “I’m sorry, but I’m just not interested” indeed a much more reasonable, mature and truthful option?

Of course! But, there is one glaring flaw in this otherwise so sensible suggestion. This reasonable, mature, truthful behaviour is the complete opposite to how we are trained to behave in everyday social interactions.

Think about it. You are invited to link with someone on social media who you don’t really want to stay in touch with. You are asked to take on an important extra task at work, while you already have your hands full. You are invited to a weekend away, but you don’t want to go. You are requested to stay on later at a meeting when you know you will consequently be late for your next meeting. Do you, politely but firmly, say ‘I’m sorry, but the answer is no’?

If so, I’ve never met you. From my experience, the standard socially acceptable behaviour seems to be to avoid the word ‘No’ at any cost.

What do you do instead? You link to the person and then quietly block them at a later date. You take on the task anyway and sacrifice your free evenings to complete it. You pretend you have to go to visit your mother that weekend, and hope that no one catches you out in the lie. You stay on at the first meeting and make embarrassed apologies for keeping everyone waiting when you turn up half an hour late for the next one. Anything to avoid having to look the person making the request in the eyes and say no, squirming as you see their hurt at your rejection, their anger at your meanness, their disappointment at your selfishness.

Saying ‘yes’ upfront then sneaking out of it later, making up excuses, sacrificing our own boundaries or letting other people down – these are our ingrained reactions. When someone actually is mature, reasonable and truthful, and politely refuses, we are shocked. One of my friends has a colleague from abroad. When asked, ‘Do you have a minute?’, she sometimes answers, ‘No’. Far from being seen as a reasonable and truthful response, this is seen as evidence of her insensitivity to social nuances and failure to adapt to our culture. Ironically, back on that campsite in France, it was my teenage egocentricity and insensitivity that made me able to handle the situation successfully. As my social awareness grew, paradoxically I became less capable of turning someone down.

We are daily conditioned to be the exact opposite of honest, clear and firm about what we want. Yet we are expected to suddenly switch on this unfamiliar behaviour when faced with a complex, emotionally charged, potentially dangerous situation. If we don’t, then when things go wrong later we are castigated for what would usually be regarded as polite and considerate social behaviour.

“I have worried I played some part in it by replying to this man, by not wanting to offend him, by worrying about him and his state of mind, perhaps even by feeling sorry for him.”

Laura Barton from The Guardian, discussing her experiences with a stalker

You could argue that we should be able to transgress the standard rules in such cases, as the stakes are higher. After all, politely submitting to an unwanted dinner at a friend’s house has a much smaller impact on your life than politely submitting to unwanted advances. But the higher stakes cut both ways. If someone feels rejected and insulted when we don’t want to eat dinner at their house, how much more rejected and insulted does someone feel when, perhaps after months of longing, they finally screw up their courage to ask us out – and get turned down?

At the same time that we get little practice at saying no, we also get very little practice at hearing it. While there are plenty of people who react badly to a rejection of their advances because they are arrogant and aggressive, there are also plenty who react badly simply because they are hurt and angry at their rejection – and have had no practice whatsoever at handling those emotions. This leads to a negative spiral: a bad reaction to a refusal makes it harder to say no in the future.

‘No’ is such a loaded word. When we hear it, we hear so much more than those two letters. We see it as evidence of the other person’s rudeness, selfishness, laziness. Or we turn it against ourselves – we are unlovable, ugly, not worthy of others. No wonder we avoid saying it to others and feel so bad when we hear it ourselves. But avoiding saying or hearing ‘No’ only causes all sorts of other problems: lies, hypocrisy, or silently letting others trample all over our boundaries. In the worst case, it can lead to a situation that spirals out of control.

Imagine we could say ‘No’ more often in our daily lives. If we could steel ourselves to the immediate social pain of being that mean person who didn’t say yes. Maybe we would experience the positive effects of honesty and clarity. We could practice saying no firmly but also pleasantly. ‘No, I’d rather not come away at the weekend as I’m not so comfortable with big groups. I’d prefer to have a cup of coffee next week, just the two of us, so we can have a good catch up’. On the other side, if we heard ‘no’ more often, perhaps we would start to place it in perspective, to see it as simply a response to the specific request rather than reading in all sorts of extra meanings. We could practice accepting a rejection, being truthful about our feelings but also understanding of the other person. ‘I’m disappointed that you won’t come as I was really looking forward to you being there. But I understand it’s not your thing, and a cup of coffee next week would be great’. Saying and hearing the word more often, maybe it would lose its taboo status and become simply what it is, the alternative to ‘Yes’.

In addition to the direct benefits of saying ‘No’ more often in everyday life, perhaps, just perhaps, it would then be easier for us to say ‘No’ promptly, loudly, firmly – but also pleasantly – to the person asking for a phone number, a date, a kiss. And – where that isn’t enough – to shout it at the top of our lungs, secure in our absolute right to use that word.