Please don’t let me be misunderstood

But oh, I’m just a soul whose intentions are good

Nina Simone, 1964

Oh Lord, please don’t let me be misunderstood

I have a recurring nightmare. Not the one where all my teeth fall out. Nor the one where I’m trying to accomplish an important journey despite having left my luggage at home (and also forgotten to get dressed). Nor even the one where a tornado is about to hit and I’m rushing to assemble all the necessities and get to shelter with the churning funnel of the storm already visible on the street outside. No, this recurring nightmare is more subtly terrifying. In it, I have done something wrong. Cheated on a test, said something hurtful, caused an accident. At least, that is what people think. I know I’m innocent – or at least that I never intended any harm – but no one is willing to listen to my explanations. All I can do is sit there listening to their condemnation – ‘selfish, devious, mean, nasty, uncaring…’.

I was brought up to be a good person. Almost equally importantly, I was brought up to worry about whether other people think I am a good person. I was taught that if an action I considered to be good might be perceived as bad, it was probably better not to do it. As a shy, awkward child with little empathy and poor social skills, divining other people’s perceptions was challenging, to say the least. But as I grew older, I learned the code for how to behave so that people perceived me as friendly, polite and considerate.

However, my nascent survival strategy faltered as the number of people I encountered grew. People from different backgrounds, different countries, different cultures. All with their own codes of behaviour, sometimes very different to the one I had so painstakingly learned. I was taught not to intrude until invited; some people see me as cold and distant. I was trained to do as I was told; some regard this as an irritating lack of initiative. Saying please and thank you and not interrupting was a core part of my upbringing, but now, living in the Netherlands, this is perceived as creepy and submissive. So I can’t fall back on a code to guide me. Even avoiding actions that might be misinterpreted isn’t safe – plenty of people perceive inaction as negative.

How can I possibly cope in this confusion, where the same behaviour might prove my good intentions to one person but be misunderstood by another as evidence of my bad character?

Explain yourself

There was a long silence. Then Dumbledore said, ‘Please explain why you did this’.

“Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets”, J.K. Rowling

Having just crashed a flying car into a valuable tree on the school grounds, I’m sure this is a highly unpleasant moment for Harry Potter. However, I’d be extremely grateful if people who feel I have done something wrong would ask me to explain. Sadly, few people are like Dumbledore. On plenty of occasions I’ve been accused by someone who either didn’t draw breath to give me the chance to explain, or didn’t listen to me when I did. Like the teacher who subjected me – as an Upper School pupil – to a tirade for being in the Lower School building and sent me packing before I could even open my mouth to tell her that the lights were broken in the Upper School toilets, leaving them pitch black. Or the mother whose little daughter had to pee in the bushes because I didn’t hear them ring our doorbell to use the toilet, who clearly believed – despite my profuse apologies – that I had deliberately chosen not to let them in. It doesn’t help that my natural response to stress situations is to freeze, so that while I am fumbling to get my brain into gear the other person is free to berate me, unhindered by my side of the story.

Not being allowed to speak or not being listened to is bad enough. But at least on such occasions I was aware that something was wrong. There have been many other incidents when I have only found out later, often from someone else, that my behaviour was seen in a negative light. It was a nasty shock during a feedback session to discover that other people interpreted my quiet shyness as cold, unfriendly and standoffish. The fear of unknowingly being misunderstood crept into my being and took root.

Now I relentlessly analyse my behaviour to see if it is open to misinterpretation. Something as simple as a trip on public transport is an imaginary minefield. If I get on the bus first, am I being rude? If I let others go first, am I annoying other people by disrupting the flow? Was I friendly enough to the driver, but not so overly friendly as to be weird? When I make room when someone sits down next to me, do they see that as a polite and welcoming gesture or do they think I am flinching away from contact with them? When I don’t sit down on the empty seat on the underground (because I already sat long enough on the bus), does the person next to the empty seat – who happens to have a different skin colour – think I don’t sit down because I’m racist?

With people who know me better, I can relax a bit more. They have longer experience of me during which I have (hopefully!) built up some credit that counts in my favour. Having never known me to behave like a bitch, for example, if I come across as bitchy on one occasion then they will be inclined to give me the benefit of the doubt and put it down to a misunderstanding rather than immediately condemn me. At the same time, much more is at stake, as the good opinion of people I live and work with matters much more to me than the spurious judgement of a stranger on a bus. So I tend to stick to a narrow, safe path. If I step outside of this, by speaking out on a sensitive subject, for example, or trying out something new, then I am overcome by a feeling of dread that their good opinion of me will be overturned. Worst of all are the situations that combine high stakes with low credit. Making friends with new colleagues, or visiting family members who I love dearly but who no longer really know me.

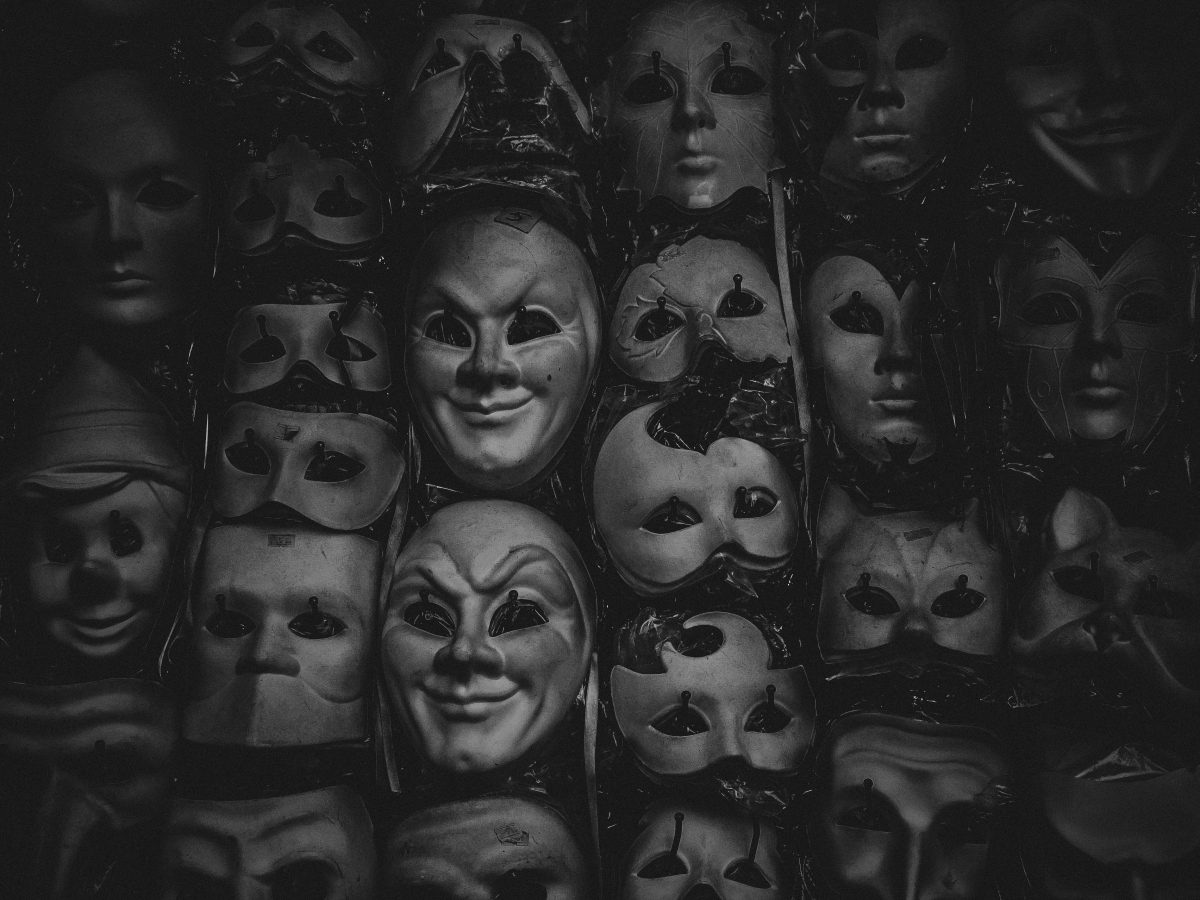

On my most paranoid days, it feels as if I am walking through a carnival hall of mirrors. Everywhere I look I see myself – not my true reflection – but the grotesque distortions that are other people’s views of me. When I make a decision, even an utterly trivial one such as choosing a different type of tea, I catch myself already justifying it so I can explain it to anyone who asks. My head fills up with a continual defensive soundtrack that I never get to present, as the criticism – real or imagined – is usually not spoken.

Of course, I don’t have to wait to be invited to explain my actions. A coach once taught me the concept of ‘subtitling’: saying out loud what you are doing while you are doing it. I’ve found this very helpful in avoiding misunderstandings. For example, saying ‘I’m just looking up some information on my laptop’ rather than inexplicably falling silent during a call. But I can’t keep up a running commentary all the time. That would be a shortcut to new misunderstandings, of the ‘crazy’ or ‘self-obsessed’ variety. Not to mention that some things are so self-evident to me that I wouldn’t even think to subtitle them.

The fallacy of explanations

…if Tony could just find a loose end and pull, a great deal would come free, for everyone involved, and for herself as well. Or this is her hope. She has a historian’s belief in the salutary power of explanations

“The Robber Bride”, Margaret Atwood

I am addicted to explanations. After all, what is this blog but the ultimate podium on which to be able to explain myself? This addiction stems from one crucial belief, a cornerstone of my worldview. If I explain my actions, then people will understand me, and will either agree with me (at best) or forgive me (at worst). With my technical background, it’s perhaps not so surprising that I believe this. However, experience has proven it to be a fallacy.

People frequently do not understand when I explain why I did something. Probably sometimes my explanations aren’t clear enough. But I think quite often people simply reject my reasoning because it’s not what they would have done themselves. Sometimes believing my explanation may threaten their security in their own decisions. A breastfeeding mother may not want to understand my reasons for switching to bottle-feeding as it potentially threatens their perception of themselves as a ‘good’ mother for breastfeeding. Sometimes my explanation may bounce off because it doesn’t target the real reason for their negative opinion of me. I can engage with the people who shout insults at me for wearing a cycling helmet and explain how I think it is safe, cite the statistics, list the examples of people I personally know who have suffered permanent damage in an accident without a helmet – but they will continue to believe I am stupid for wearing a helmet as for them, it’s the social stigma that counts. Sometimes – I suspect – people simply prefer to think badly of me, for whatever reason.

Similarities and differences in background and outlook matter a great deal in mutual understanding. The more similar someone is to me, the more chance that they understand my actions. The more different, the more chance that they are bewildered by them. That gap in understanding is then often filled in based on prejudice. My shyness is a case in point. Men may think I am silent because ‘a woman lacks the knowledge to join in a technical discussion’. People with a different skin colour may think I’m silent because I’m a snooty racist. Extraverts may think I am silent because I have nothing to say. Some of these prejudices may be based on prior bad experiences with people ‘like’ me. So the prejudice is not their fault – but it isn’t mine either.

Escaping the maze of mirrors

Good intentions, constant alertness, explanations and subtitling can help me, but they won’t save me. No matter how much I beg for the mercy of a higher power, the fact is that I will frequently be misunderstood. There will be people in the world who think I am stupid, arrogant, selfish, racist, boring, snobbish, disgusting – the list is endless. This causes me pain, but I have to accept it.

There are three things that perhaps can help me – and anyone else who feels lost in the maze of mirrors:

The first is to remember that even when others think badly of me, it does not necessarily follow that I am a bad person.

The second is that the mirrors are not one-sided. I regularly judge people myself, only realising later that I had completely misunderstood them.

Finally – and perhaps most importantly: most people couldn’t care less what I do. Far too often, the mirror exists only in my own head.